Thought Leadership

The Role of Data in Sporting Director Hires: 5 Rules

12 MIN READ

Thought Leadership

Inspired by what you’re reading? Why not subscribe for regular insights delivered straight to your inbox.

Once a topical debate, the value of a Sporting Director or equivalent is now accepted by most clubs. All 20 Premier League teams currently have a sporting or technical director in place, with similar trends across most major competitions. Whilst the role itself can vary, finding the right candidate is a critical lever for ensuring sustained success on and off the pitch.

When it comes to executive searches, football clubs have one key advantage over most industries: access to performance data at-scale. Recent developments have dramatically expanded potential insights into prospective hires, far beyond the high-level or self-selected data available in other sectors.

However, scale creates complexity and optionality. This article shares 5 core rules for data-led searches, based on TFG’s ongoing work supporting clubs around the world. We then apply these to an illustrative club to identify some of the top directors in today’s game.

Rule 1: Dedicate real resources to the search, reflecting potential impact

Top sporting directors have proved their ability to be transformative. Resources allocated to the search should reflect this potential – whether this is money, search time or management capital.

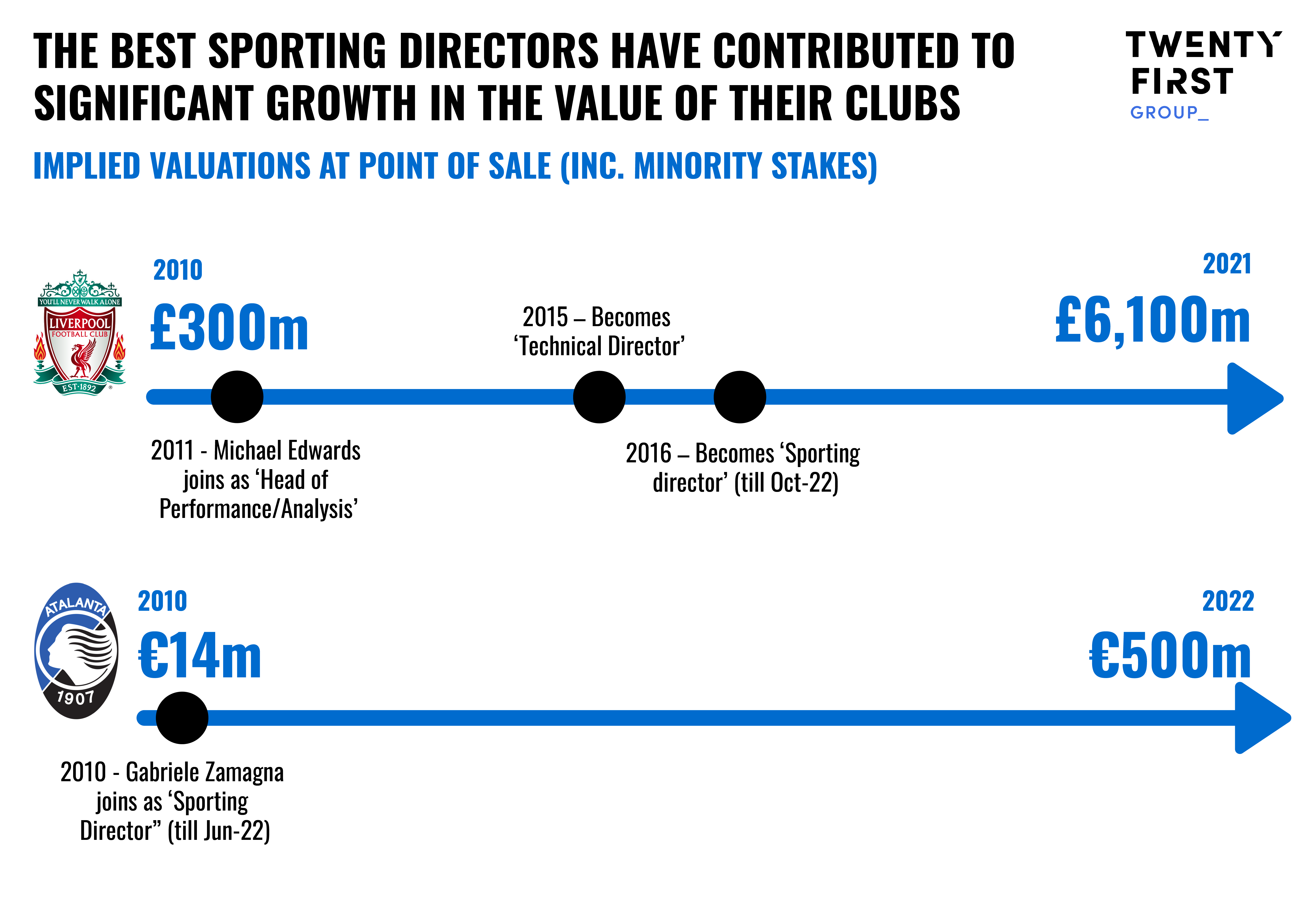

Micheal Edwards (Liverpool) and Gabriele Zamagna (Atalanta) are notable examples. Despite being famous for on-pitch turnarounds, they’ve delivered more than titles and Champions League places, with both clubs seeing 20-35x valuation growth over their tenures. Meanwhile clubs with declining sporting performance can often see valuations stagnate or fall.

Moreover, we find overachieving clubs in Big 5 leagues have had sporting directors in post for almost 9 years on average, reflecting the strategic importance of getting this role right (overachieving clubs = those outperforming our predicted level given spend).

Rule 2: Look beyond typical measures when evaluating on-pitch performance

Football is more uncertain and contextual than most sports; single low-probability goals swing titles and points across competitions aren’t equal. Smart clubs therefore go beyond metrics like “Number of promotions” or “Points average”, and might include the following:

- Contextual performance factors – Such as the strength of competition, margin of victories and underlying performance statistics (e.g. xG). For example, we use the TFG World Super League model to evaluate true club performance, a single metric evaluating all clubs on the common scale using a wide range of inputs.

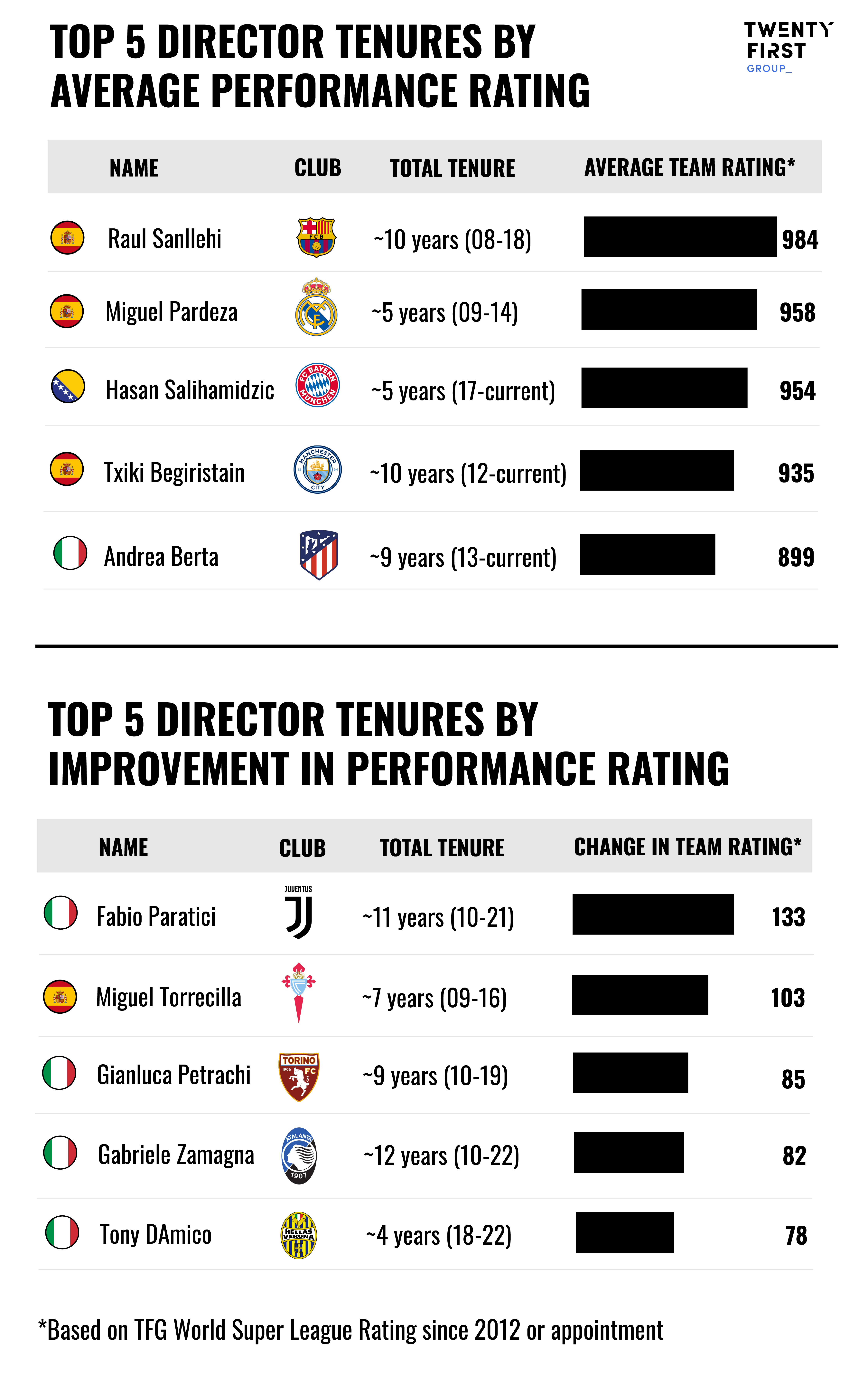

- Starting point – Performance needs to be measured alongside a director’s starting point. Based on our World Super League Model, Sandelli’s Barcelona and Pardeza’s Real Madrid were predictably the two tenures with the highest average performance (see chart below). However, Fabio Paratici’s tenure at Juventus represents the biggest uplift in performance over the last 10 years. Paratici joined the club after 2 consecutive 7th place finishes, then went on to win 9 consecutive Serie A titles and challenge the best clubs in Europe. Torrecilla’s Celta de Vigo and Petrachi’s Torino were also impressive, with an overall improvement roughly equal to the difference between an average Europa and Champions League team.

- Resources available – The best searches will also evaluate performance data alongside information on wage and transfer spend.

Rule 3: Quantify off-the-pitch impacts

The modern sporting director’s remit often extends beyond on-pitch results. Clubs with finite resources will benefit from individuals capable of generating value through the player trading market, which can then fund reinvestment. Indeed, new financial fair play regulations mean this is increasingly a concern, even for football’s richest clubs (though the importance vs performance will inevitably vary).

Clubs can evaluate this through a number of metrics. Though notable examples include net transfer income, squad value growth or the extent to which directors have negotiated fees beyond ‘fair market value’ (used as part of our worked example below).

Rule 4: Tailor criteria to your own priorities

Most things are measurable, but priorities will naturally differ by club. For instance, Manchester United will care less for net revenue creation than Benfica. Some clubs have a vision for a specific style of play and want a sporting director who can drive a common approach. Others will prioritise academy success, and a proven ability to develop homegrown talent.

Consequently, we tend to help clubs build bespoke indexes, or single metrics assessing every candidate’s suitability against the team’s own priorities (see worked example below).

Rule 5: Combine with non-data elements

Data should augment traditional recruitment methods, not replace them. Its main advantages are objectivity and scale, allowing clubs to create better informed shortlists. However, no metric is ever complete. A pure-data approach can miss non-traditional candidates, and follow-up interviews can help a club better understand questions like:

- What influence did he/she have over observed club success?

- What is their underlying approach and principles?

- Is there an unknown reason for poor scoring in a certain criteria or time period?

- What working culture do they foster at their clubs?

Worked example – Top 6 directors for ‘Club X’

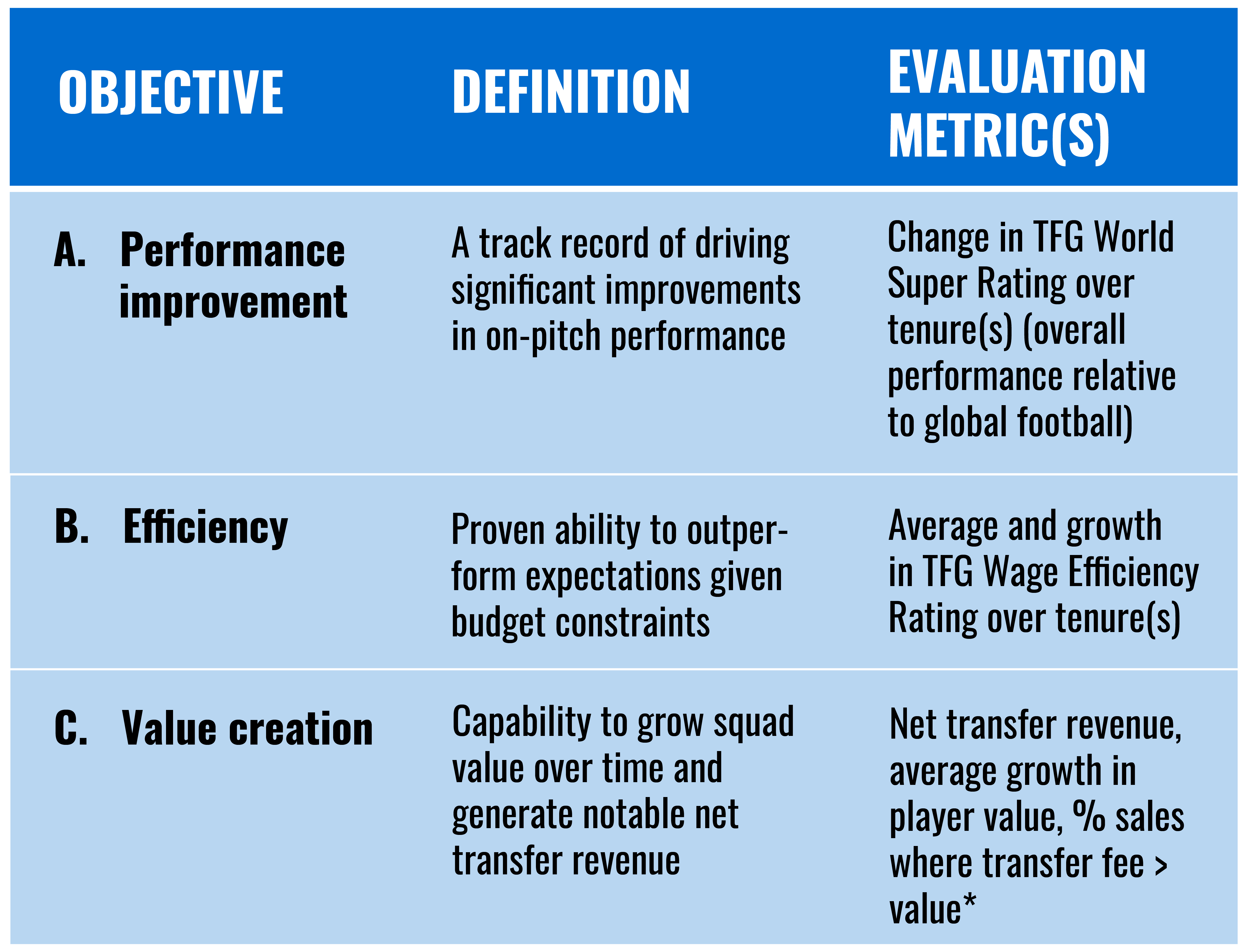

So who are football’s best performing sporting directors? In line with ‘Rule 4’, this depends heavily on a club’s priorities. For this example, let’s imagine a leading “Club X’ has the following objectives (of equal importance).

*You can find out more about price vs value here.

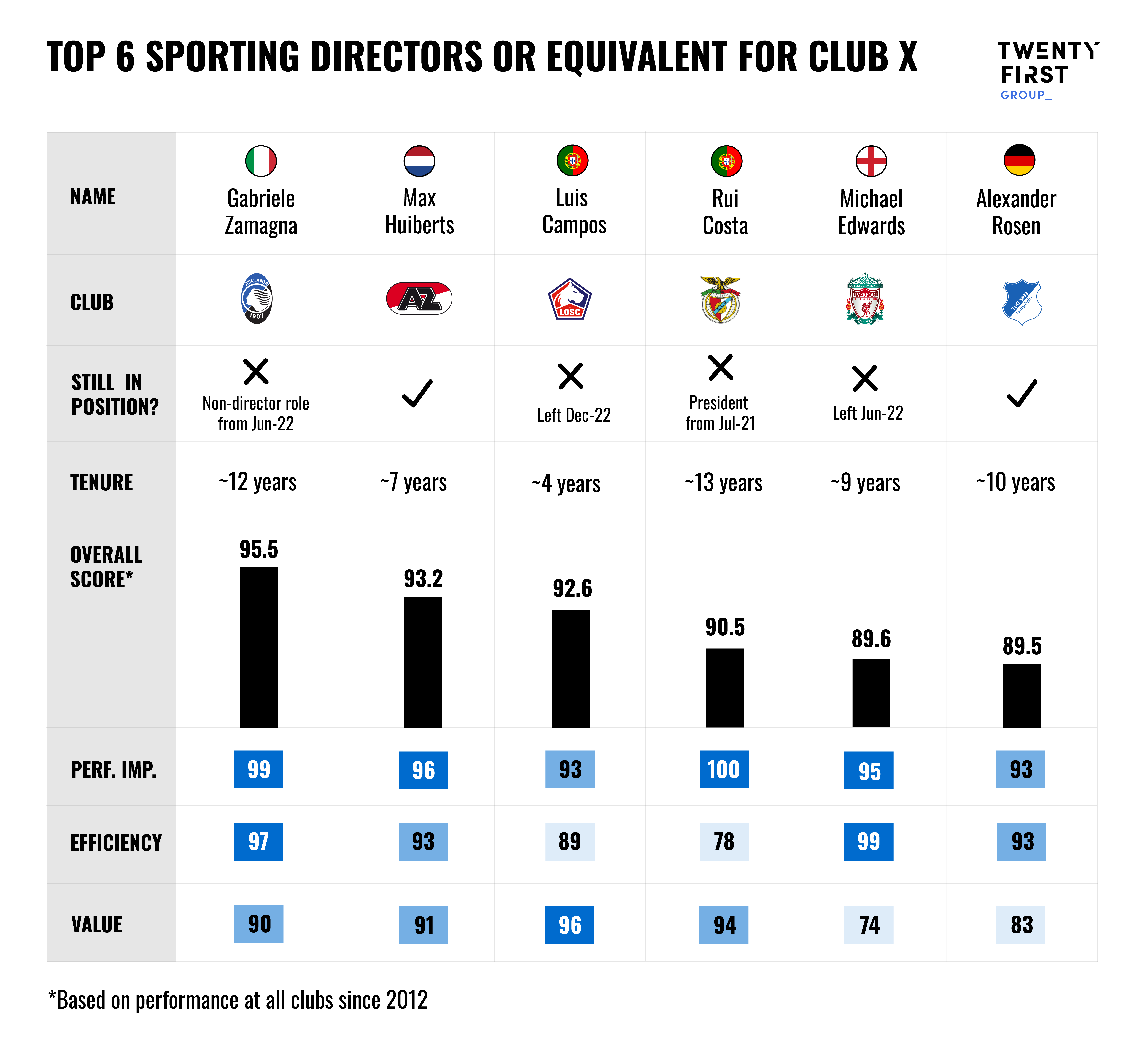

Using this criteria allows us to identify the following top candidates:

Gabriele Zamanga and Micheal Edwards are 2 predictable names, mentioned already. Zamanga earns the top spot in this ranking given his ability to drive Atalanta’s remarkable performance improvement with relatively few resources, and create significant value in the process.

Other notable mentions go to Max Huiberts of AZ Alkmaar (2nd) and Luis Campos of Lille (3rd). Huiberts’ Alkmaar have consistently challenged the best teams in Eredivisie and qualified for Europe, despite a small relative wage spend. One reason is their leading academy pipeline, with the club making >$45m in 21/22 from the sales of 3 academy players alone. Meanwhile, Campos’ Lille narrowly escaped relegation in his first season but went on to win a Ligue 1 title in 20/21. Off the pitch, he created significant funds for the club through an ability to buy and sell at value, generating >€100m in net revenue from the sales of Pepe and Osimhen for example.

Of course, ‘Rule 5’ means these results only provide an indication of the best candidates. An extended analysis might consider the top 100 candidates and use additional filters to arrive at a shortlist for interviewing (e.g. likelihood of leaving current position, expected wage demands, language constraints).

In conclusion

Data provides a powerful and underutilised tool within sporting director searches, but must be used smartly to deliver impact.

For more information on TFG’s Performance Intelligence services please contact Omar Chaudhuri.