Thought Leadership

What could an alternative World Cup format look like?

12 MIN READ

Thought Leadership

Inspired by what you’re reading? Why not subscribe for regular insights delivered straight to your inbox.

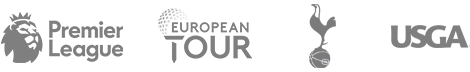

With the next edition of the FIFA World Cup imminent, we wanted to look at how the format influences the outcome of the tournament. In much of our Competition Intelligence work, we use the format as a lever to grow commercial value – the format enables competition organisers to create more content through changing the number of matches, to influence the attractiveness of those matches or to change the rhythm of a competition through allocating jeopardy to the most meaningful moments.

We have previously explored the latter example in the world of tennis, where the men’s Grand Slams allocate jeopardy to the latter stages of the tournament through playing five sets instead of three. The longer format means quality is more likely to prevail making early rounds predictable but the latter rounds are higher quality and more evenly matched. Conversely, the three set format in the women’s game allocates jeopardy to the early rounds, with the shorter format increasing the chance of weaker players causing an upset, with the downside of limiting the prospect of a heavyweight clash in the final.

As for the FIFA World Cup, the existing format is highly effective. Groups involving 4 teams where two progress means the number of dead rubbers across the tournament is limited. The seeding ensures that the best teams are given a fair chance to progress, meaning heavyweight clashes at the climax of the event are likely, while the knockout rounds provide jeopardy through giving smaller teams who qualify from the group stage a chance to spring a surprise, as Russia did to Spain in 2018 or as South Korea did in 2002, knocking out both Italy and Spain before being beaten by Germany in the semi-finals.

Upsets are among the most interesting moments in any competition – ‘David vs Goliath’ narratives are among the most compelling for fans. With this in mind, we decided to look at alternatives that might increase the chances of football’s ‘David’s’ prevailing more regularly.

As we know, knockout football requires a way to separate teams who are level at the end of normal time. The away goals rule was the preferred method for UEFA when playing knockout ties over two legs, but in the World Cup it’s 30 minutes of extra time followed by penalties. The use of extra time generally makes matches more predictable – the longer the game the more likely it is that quality will prevail. We therefore simulated the impact of removing extra time from the knockout stages of the 2022 World Cup, with teams going straight to penalties.

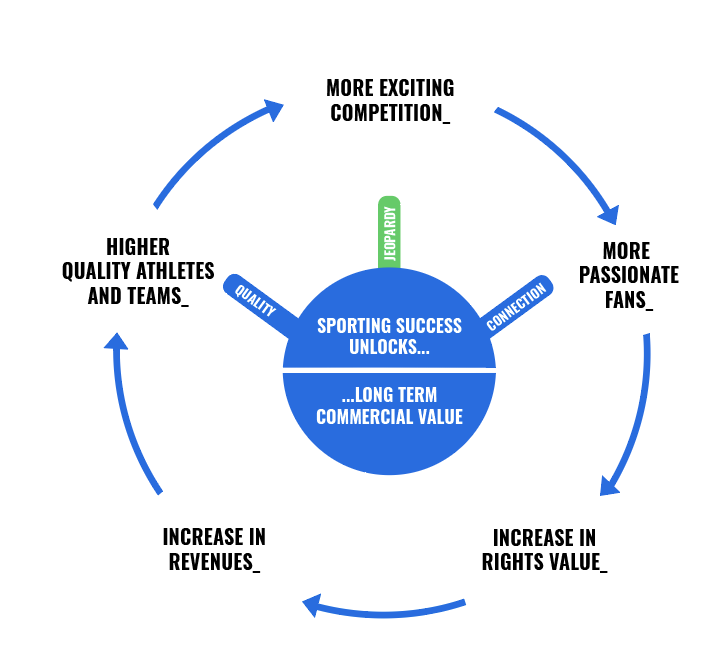

On an individual team level, the influence is small given it requires teams to go to extra time in a knockout game to have an impact – something that happens around 1 in 3. For example, it decreases the favourites – Brazil’s – chances of winning from 23% to 21%. Likewise, it generally increases the chances of an underdog team progressing deep into the tournament. Individual teams are influenced by their draw, but generally the change favours the smaller teams.

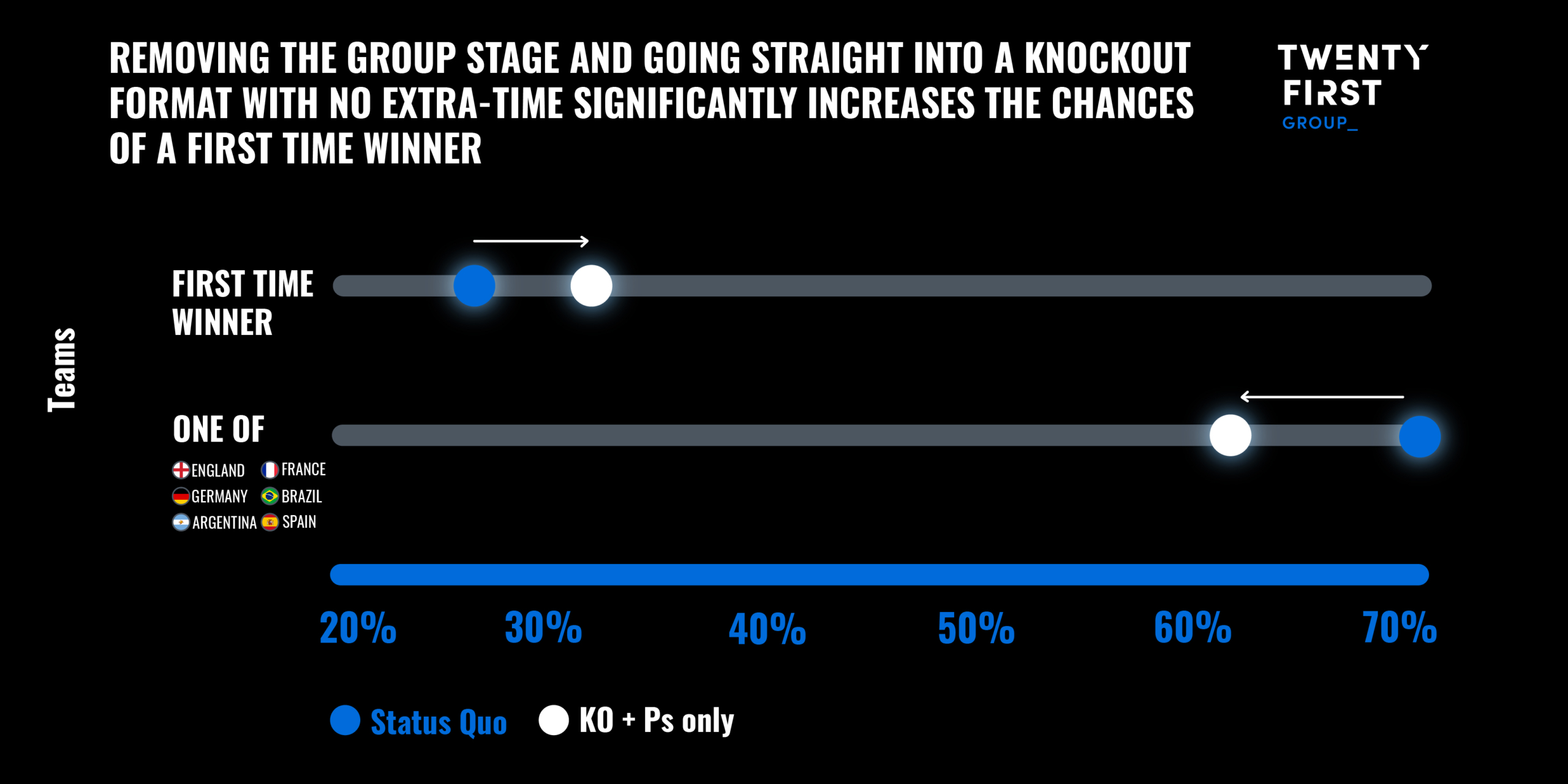

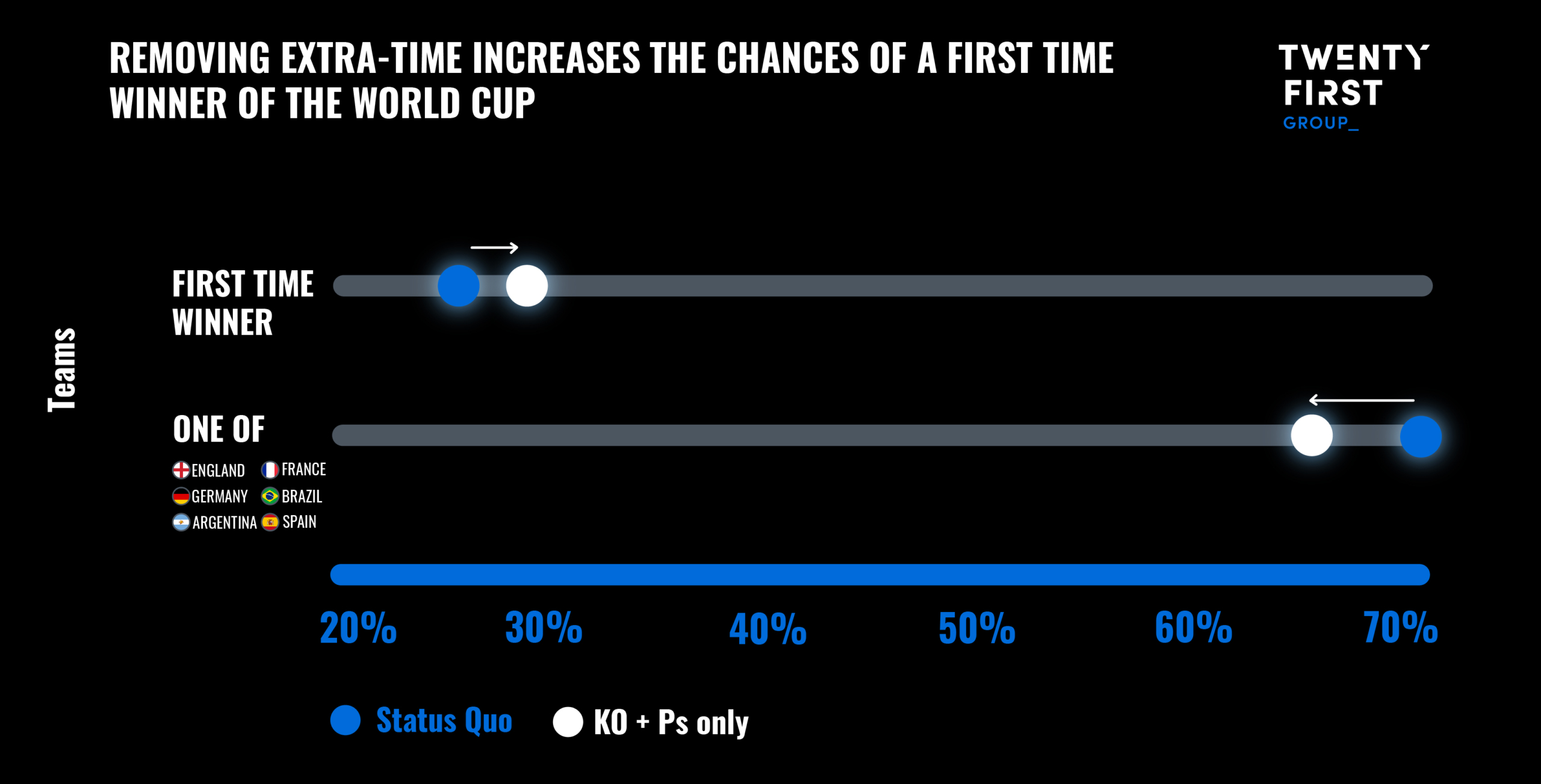

The impact is more pronounced when reviewing outcomes at an aggregate tournament level, with the chances of a first time winner increasing, as the chances of one of the traditional favourites winning falls:

Overall, the impact is small but slightly increases the chances of an upset while also saving fans from sitting through negative football that is usually served up due to extra time. We project that 45% of games that go to extra time have zero goals – perhaps teams would be more likely to play positive football were they faced with the prospect of going straight into penalties.

Group stages vs knockout

The other aspect of the format that we have ripped up is the group stage. In reality, this would be a bad idea for both sporting and commercial reasons. The group stage has significant benefits – not least guaranteeing each team three matches, providing a worthwhile reward for qualifying and making the trip to Qatar, creating more matches and therefore more content for broadcasters and fans, and giving the tournament a chance to build momentum and build narratives. Nevertheless, we have quantified the impact of scrapping the group stages in favour of a single-leg knockout format, complete with a randomised draw and the removal of extra time, as above.

As expected, the impact is a little more significant. Brazil’s chances of winning the tournament drop to under 20%, while the chances of a ‘fairytale run’ increases.

Generally, the knockout format favours the underdogs – meaning those teams who are favourites to progress from their group either don’t benefit or actively suffer. Senegal, for example, suffer as a result of this change in format largely due to their good fortune of being drawn in the same group as hosts Qatar, who are rated as the worst team in the competition. Qatar have the smallest chance of winning the tournament despite the benefits of home advantage – something no reasonable change in format is likely to influence. Similarly, USA are not positively impacted due to their being favourites, along with England, to progress from their group at the expense of Wales and Iran. Wales, by contrast, benefit from the increased randomness that the knockout format promotes, while of the selected teams, Japan are the biggest beneficiary given the difficulty of their group including Germany, Spain and Costa Rica.

On an aggregate basis, the knockout format promotes greater randomness – with the chances of a first time winner being around eight percentage points higher. Similarly, the tournament being won by a team other than Brazil, Argentina, Germany, England, France and Spain increases to over 35%.

The knockout format increases randomness and therefore makes the tournament a little less predictable which is generally a good thing. But the damage is untenable – reducing the number of matches, limiting the chances of narratives to develop as the tournament builds momentum and meaning half the teams would leave having played – and lost – just one match.

The existing format has a good balance of quality, jeopardy, sporting credibility and commercial value based on the number and type of games the format delivers. Perhaps further scrutiny of the format for the next edition is needed, however. In 2026 the format will change to accommodate 48 teams and the impact on jeopardy will be a key factor in its ability to emulate the success of past editions. But that is for another day.

If you would like to find out more about our competition intelligence services, please get in touch with Ben Marlow.

![TFG - LinkedIn Graph Templates - 250922 [Recovered]-25](https://www.twentyfirstgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/TFG-LinkedIn-Graph-Templates-250922-Recovered-25-scaled.jpg)