Thought Leadership

Jeopardy where it counts: how the competition format can grow tennis’ commercial value

9 MIN READ

Thought Leadership

Inspired by what you’re reading? Why not subscribe for regular insights delivered straight to your inbox.

Novak Djokovic lifting La Coupe des Mousquetaires following his epic five set victory over Stefanos Tsitsipas in the final of the French Open felt like a coronation for the greatest player of all time. And coming back from the brink – two sets to love down against the inspired Greek – to prevail in the Championship match was not even his biggest achievement of the week. Taming 13-time champion Rafael Nadal in the semi-final was generally considered the finer accomplishment such was the quality of the match and the Spaniard’s dominance on clay. With 19 Grand Slam titles, Djokovic is one behind the other giants of the era, Roger Federer and Nadal himself, but with age on his side and as the only man with two Grand Slam titles across each surface, it is likely that he’ll be formally crowned the GOAT once he hangs up his racket for good. But Serena Williams, the undisputed champion of the modern women’s game, is perhaps more deserving of that crown and because of, not despite, her 23 (and counting) grand slam titles having been won over three sets.

At Twenty First Group, we believe that sport is most compelling when it consistently delivers quality, jeopardy and connection. Men’s tennis in the modern era is a fine example. The ‘big three’ are among the highest quality exponents of their craft across any sport, their catalogue of dazzling duels have kept fans on the edge of their seats for more than a decade – Nadal and Federer’s magnum opus in the 2008 Wimbledon Final perhaps stands the tallest among giants – while their success, contrasting styles and personalities have connected both them and the wider game of tennis to fans across the globe.

In contrast, the accomplishments of Williams are generally not held in such high regard despite her having won more grand slam titles (23), partly because they have been won over three sets. It is generally accepted that any comparison between her 23 grand slams and Djokovic’s 19 is not like-for-like. The usual argument, however, is that winning over 5 sets is the greater challenge, leading many to conclude that Djokovic’s 19 are actually worth more than Williams’ 23. This is simply wrong. That Williams has won 23 slams over three sets is an argument in her favour. Yes, five sets is more tennis and is therefore more tiring, but it is actually easier for the strongest players to win over longer formats.

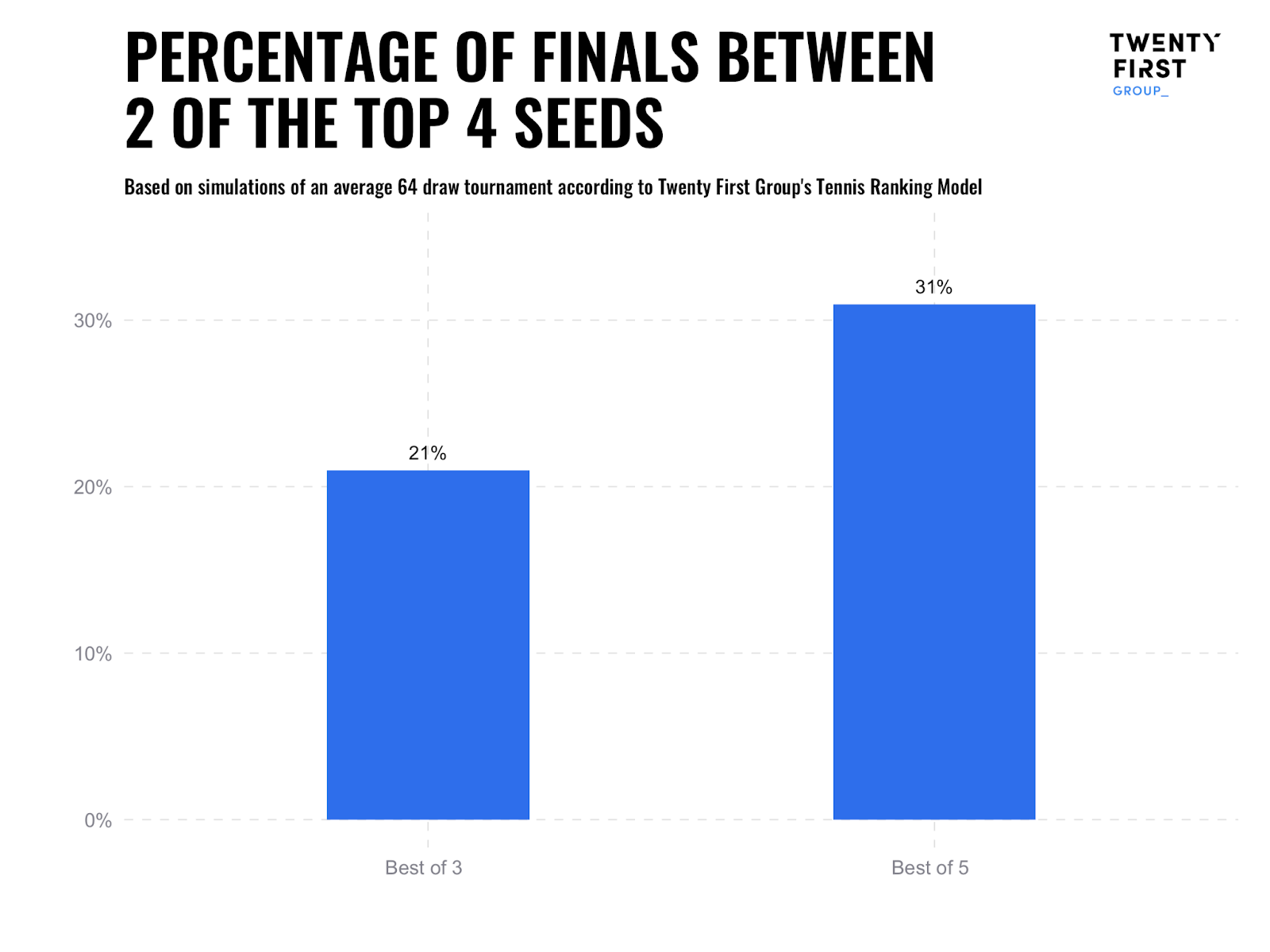

The logic behind this is simple – the longer the match the more likely it is that the best player will triumph. This is true of any sport. Manchester City are more likely to finish above Crystal Palace in a league football season than they are to win a one-off match. More time means more opportunity for quality to prevail, limiting randomness. This means that the five set format is more predictable, with the best players more likely to win. Based on our simulations, the best player is likely to win a five set tournament around 31% of the time, relative to 23% for the best player in a three set tournament.

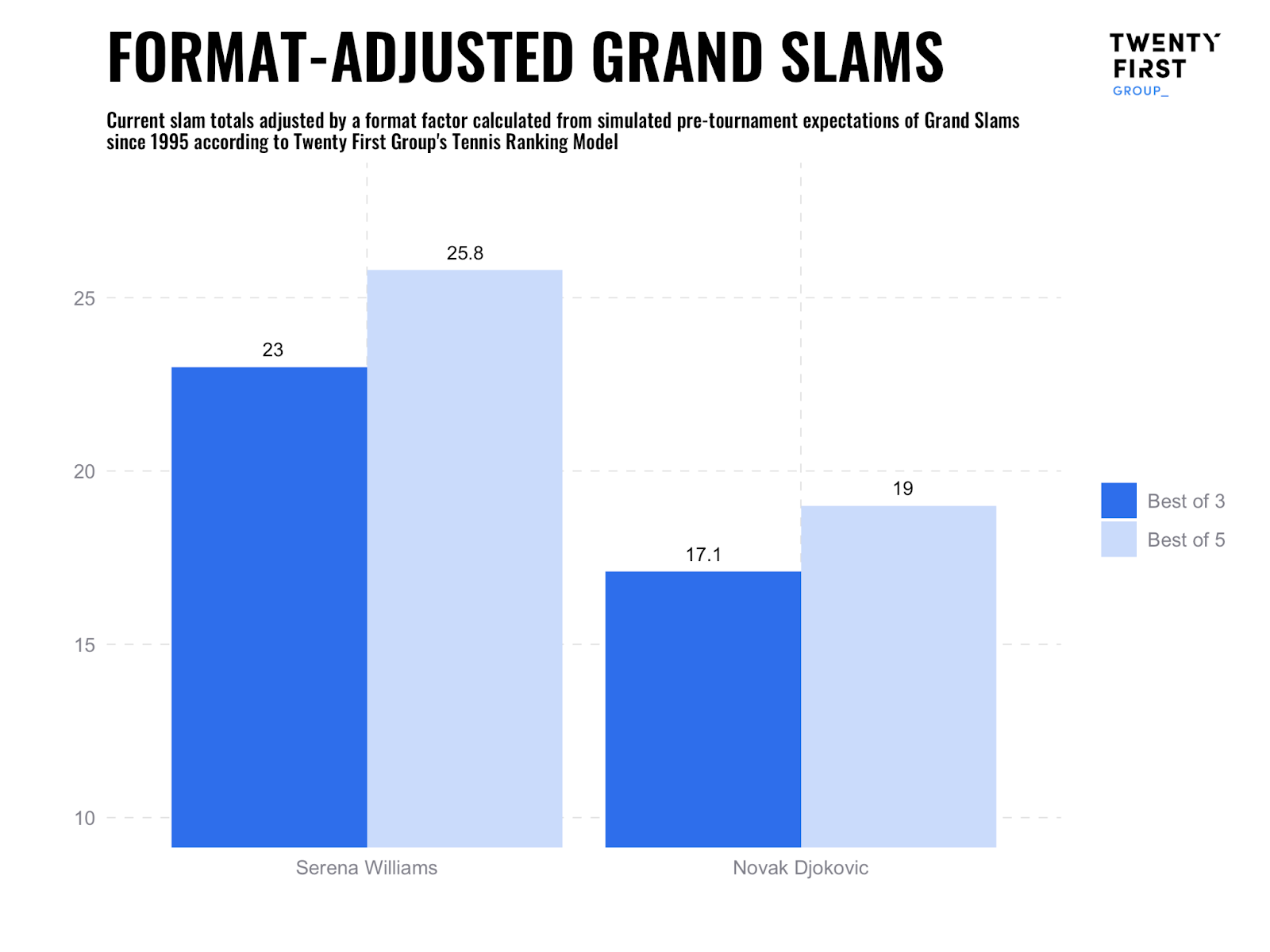

Given that Williams has been the strongest player at the vast majority of tournaments that she has entered, playing over five sets would have suited her. To prove this, we used our Intelligence Engine to simulate the performance of both Williams and Djokovic at every grand slam they played, but with the formats swapped (i.e. with women playing over five sets and men three). In this alternative reality, we estimate that Williams would have a total of 25.8 slams on average, while Djokovic would have only 17.1. The misconception that winning over three sets is easier acts as an inappropriate anchor on any appraisal of Williams’ and her peers’ claim to greatness.

That’s not all. The three set format in the women’s game has also limited the narrative value of Williams’ success and therefore the connection that fans have with Williams and the women’s game. The five set format adopted at the Grand Slams has allowed the titanic battles between the ‘big three’ of men’s tennis to assume epic status – an opportunity not extended to Williams. Five set thrillers are thrilling, in part, because the effort required of the players gives the impression of higher stakes and greater uncertainty (jeopardy), and the duration of a five set match creates an ebb and flow that lends itself to better storytelling, growing fan fascination (connection). The shorter format has stymied the story-telling quality of Williams’s great victories, meaning they stick less long in the memory, limiting the chances for her on-court brilliance to translate into compelling narratives and, therefore, connection with fans.

This has been exaggerated by the absence of a great rival to add further narrative value to her career, the prospect of which has also been undermined by the shorter format. The greater chance of upset in the early rounds means that the tournament’s strongest players are less likely to meet in the final, limiting the chance for rivalries among the game’s strongest players to develop over time. Our tournament simulations bare this out with the five set format producing a final between the tournament’s best players significantly more often than the three set format.

This has played out in the development of the rivalry of the big three – the format having given them greater opportunity to meet when the stakes are highest; Djokovic has faced his three closest rivals (Federer, Nadal, and Murray) 40 times in Grand Slam semis and finals, compared to just 20 meetings between Williams and her most familiar competitors (her sister Venus, Victoria Azarenka, and Maria Sharapova) in the latter stages of the majors.

This matters not just for fans – and the overall discussion of GOATness – but for commercial reasons too. Sponsors and broadcasters benefit from the development of stars and rivalries, and their progression deep into the meaningful stages of tournaments. For the format to hinder this in the women’s game short-changes all parties. Instead, using the format to allocate jeopardy where it is most valuable – in the latter stages – would make sense from both a sporting and commercial perspective. The likelihood that the big players will reach the latter stages and have an epic, high-stakes battle when they meet has underpinned the golden age of men’s tennis and the commercial growth that has followed. Women’s tennis, and tennis more generally, has a significant opportunity to mine the rich seams of value that historic formats have kept from view.

A pertinent case in point, en route to victory in this year’s French Open Djokovic came back from two sets down twice. His having done so has been part of the narrative about his genius, his success founded on an unequalled resilience and desire to win. But were he playing over three sets, as Williams has her whole career, he would have been out in the fourth round depriving us of his battle-for-the-ages with Nadal in the semi-final and yet more evidence of his greatness. While his qualities are indisputable, he and his male contemporaries have benefitted from a competition format designed to reward their quality – a luxury not permitted to the best players in the women’s game. With equality in prize money at the Grand Slams, perhaps it’s also time for equality in format, and with it the opportunity for players of either sex to be considered the GOAT.