‘Stretching the pyramid’: how federations can deliver systemic over-performance

National underperformance tends to drive predictable headlines. ‘Investment’, ‘participation’, or the ‘end of a golden generation’ are our usual fail-safes, but they mask the fact that many nations consistently overperform relative to their population and resources.

Sustained overperformance is rarely down to luck, but a result of a deliberate and increasingly ‘data-driven’ strategy. It comes from building a high-performance ecosystem that is more efficient and effective than its rivals. The core question for most federation leaders should not be, “How big is our player pool?”, but “How effective is our system at turning potential into world-class performance?”.

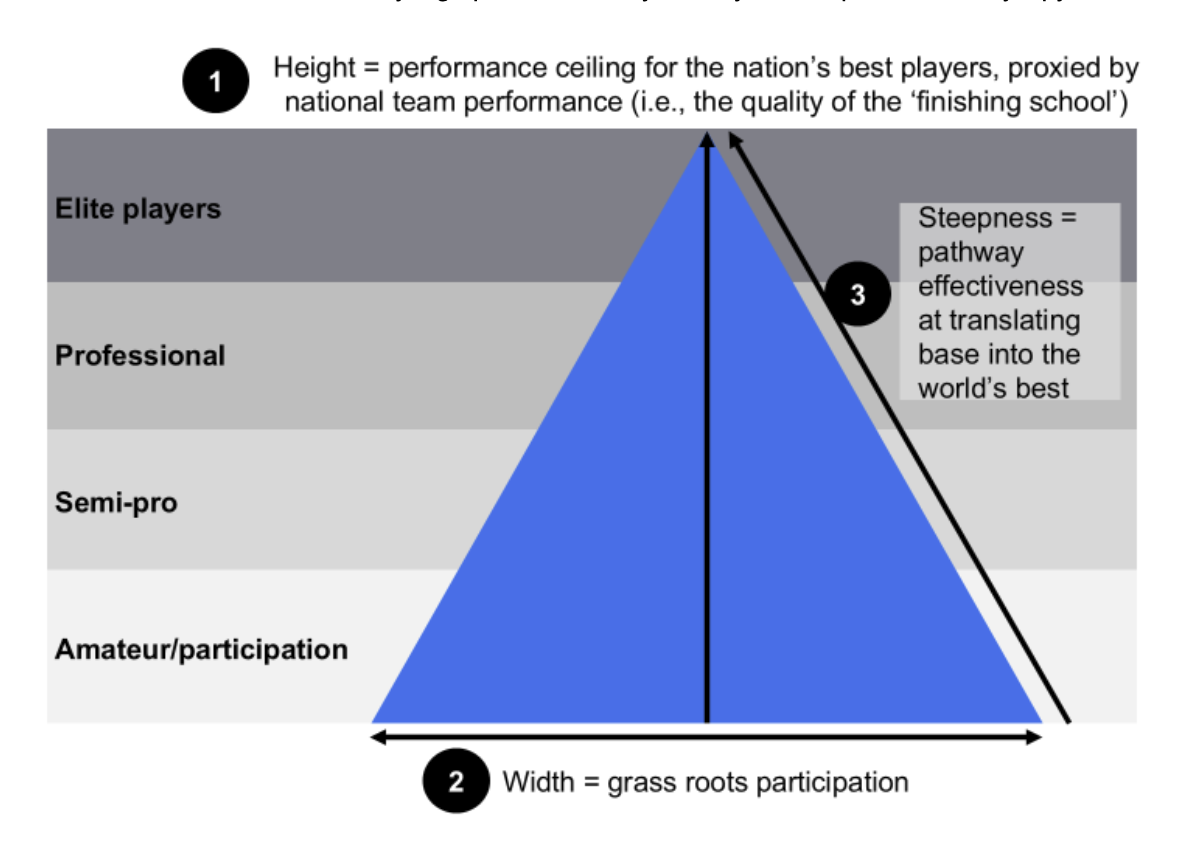

How Can We Evaluate Effectiveness? The Sporting Pyramid

We assess the effectiveness of any high performance system by the shape of a country’s pyramid

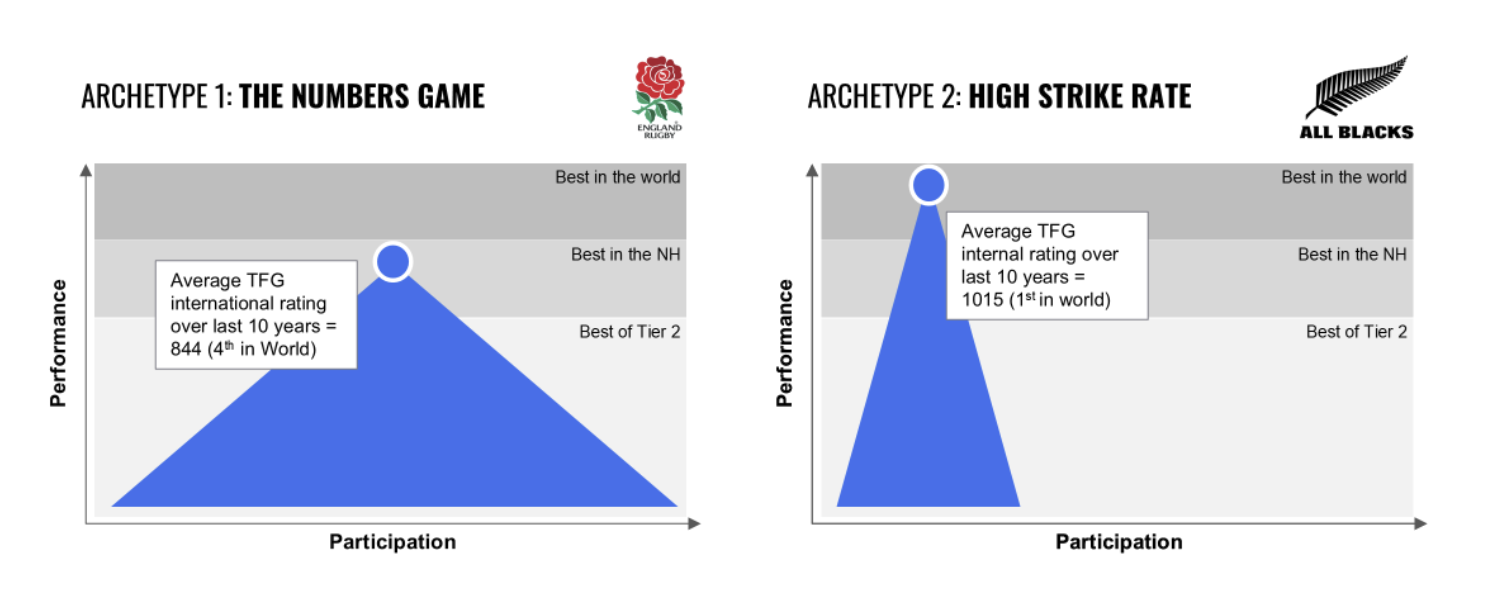

Examples of Over-Performance (The ‘Stretched’ Pyramids)

Men’s Rugby

New Zealand’s All Blacks are perhaps the archetypal example of a “stretched pyramid”, dominating international rugby for decades despite having a participation base that is 10-15% of England. The core difference is not the conversion of participation into professionals, but the system’s ‘strike rate’ in transitioning its professional players into the world’s best.

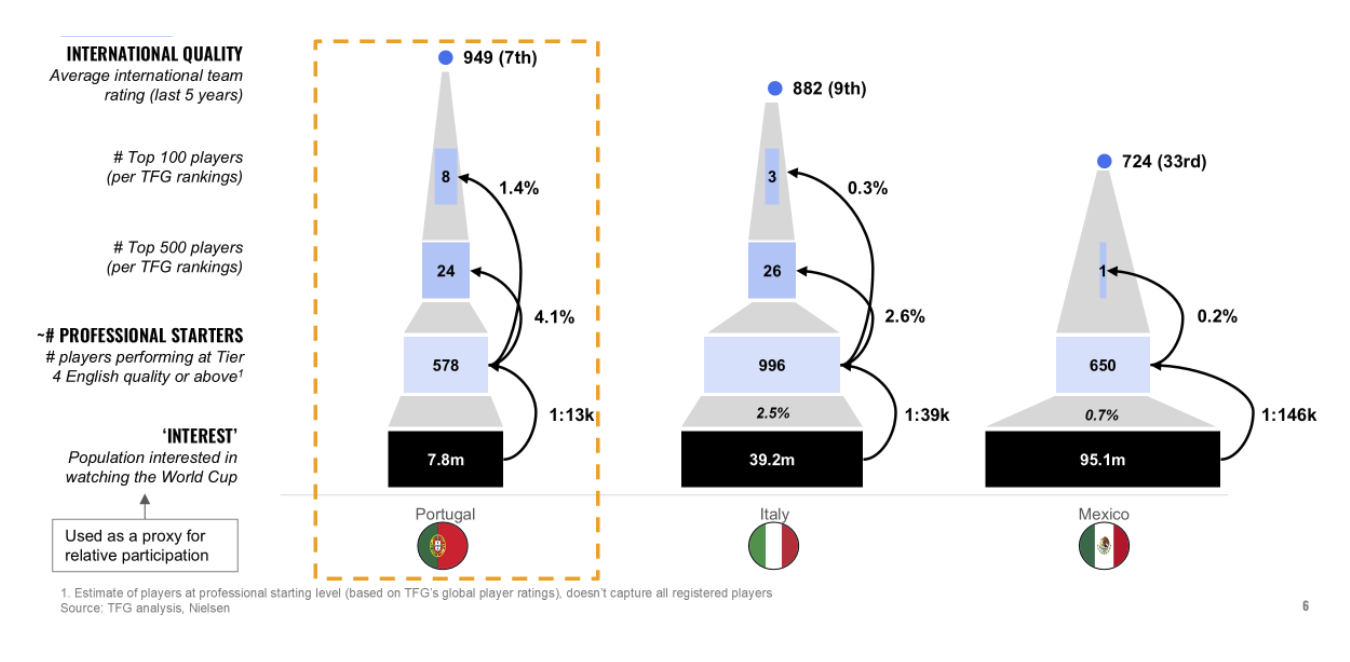

Men’s football

The sheer scale of men’s football participation makes it difficult to be the world’s best without a significant base. Nations like Brazil, France and Spain have been consistently high performing, but they are all underpinned by vast participation.

True overperformance, therefore, is most evident in the ‘best of the rest’. For example, Portugal has significantly outperformed Italy in their production of elite talent over recent years despite having a 5x smaller base. The gap is even larger when comparing this output to a nation like Mexico, which exemplifies a ‘wide base, low peak’ pyramid: Mexico produces a high quantity of professional players but has historically struggled to convert them into higher quality players.

Portugal’s core advantage lies in its elite talent strike rate, with the system ranking 1st in the world for its conversion of professionals into top 500 and top 100 players per TFG ratings (4.1% and 1.4% respectively).

Comparing Portugal and the All Blacks also demonstrates the ability for different approaches to yield results. Most Portuguese players finish their development path in foreign competitions (after spells in some of the world’s leading academies), whereas the New Zealand system specifically prohibits players from playing internationally.

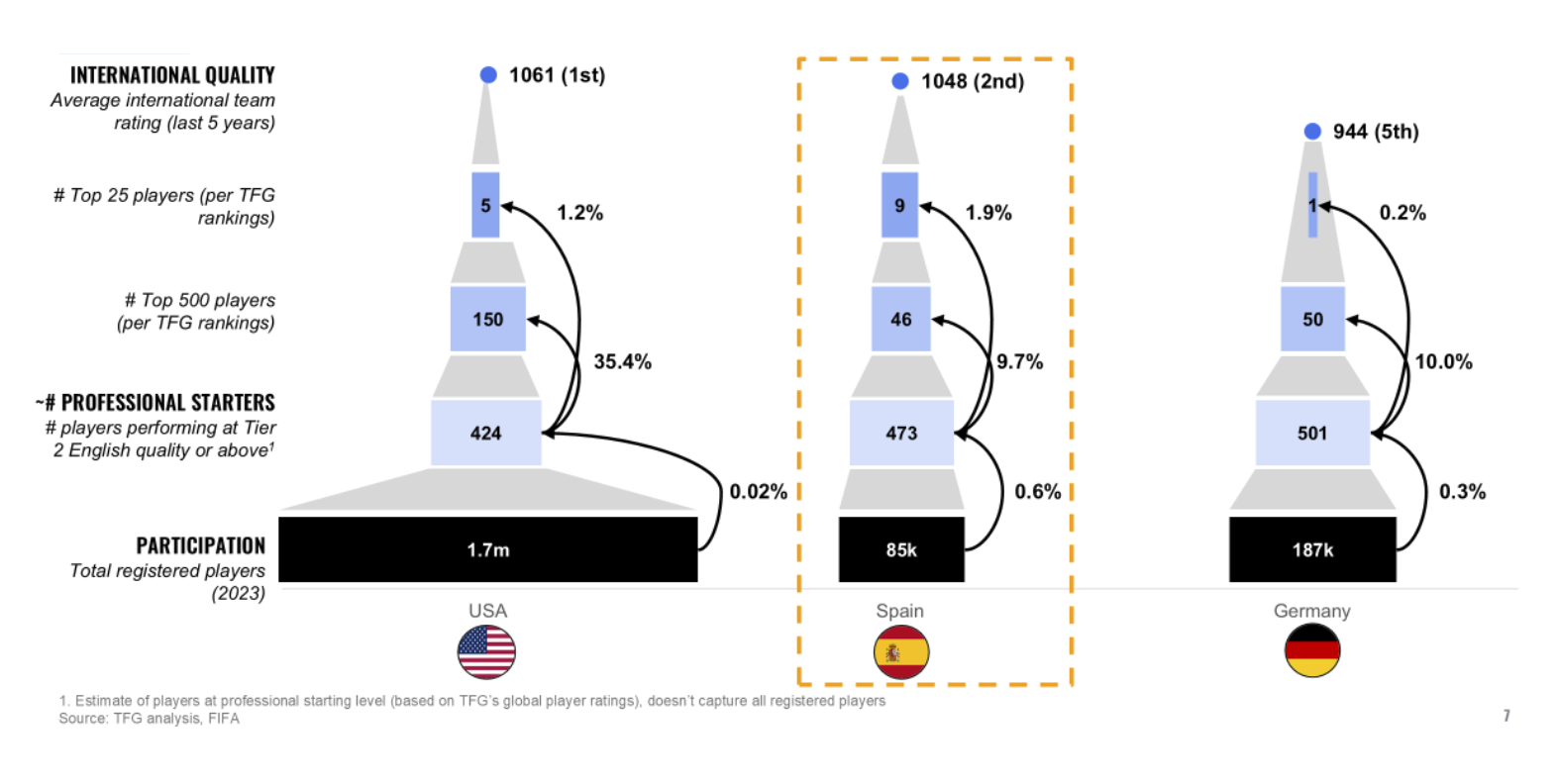

Women’s football

The US occupies a unique position in women’s football, with an established pathway from grassroots through to the collegiate system that ensures a far deeper pool of officially registered players. Despite an early 2023 World Cup exit, they remain the world’s best-performing international team based on our long-term holistic performance models.

Spain is the prime example of ‘stretching the pyramid’ in the modern women’s game, challenging US dominance despite a 20x smaller official participation base. Whilst the US system remains world-leading at generating top 500 players, Spain has driven a competitive advantage in their ability to develop ‘the world’s best’ (with 9 of the current top 25 players, vs 5 for the US). This is likely a trade-off of two opposing domestic structures: an NWSL system designed for parity, which allocates investment and talent broadly across many strong clubs, versus a Liga F system where resources are overwhelmingly concentrated in two ‘super clubs’. The data confirms this divergence: 74% of Spain’s 2023 World Cup squad was drawn from Barcelona or Real Madrid, whereas the top two feeder clubs for the US squad only contributed 39% of players. Concentration on this scale also drives cohesion at an international level, allowing the group of individual players to outperform expectations as a combined group.

These nations prove that performance is not a simple function of population or participation. Nor is it intrinsic to a country’s overall approach, with different winners across sports and genders.

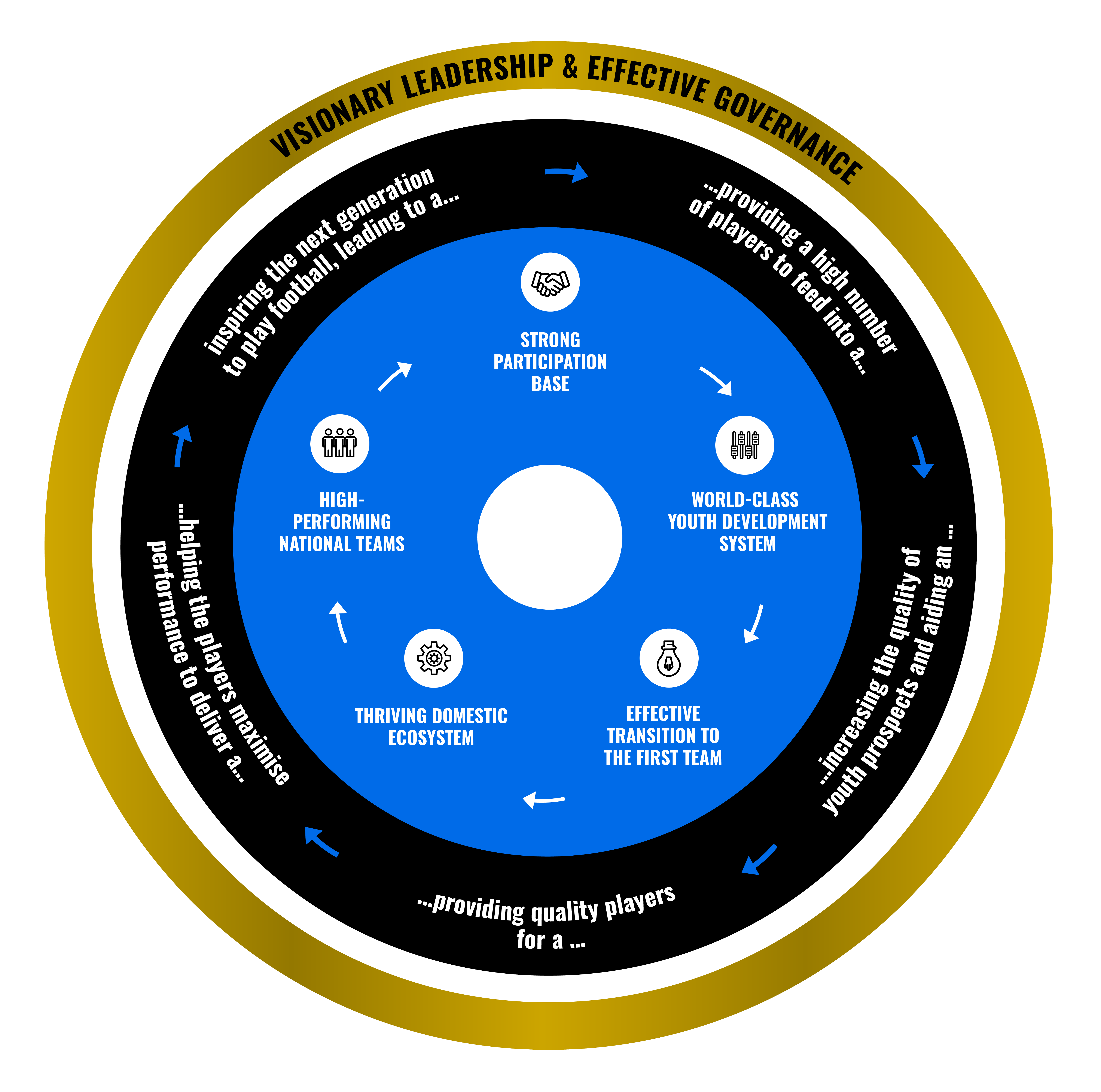

How Federations Can Stretch the Pyramid: The Virtuous Cycle

Systemic over-performance is achieved by creating a virtuous cycle—a high-performance ecosystem where all parts are connected and mutually reinforcing.

Our experience supporting global federations has defined the five key pillars required to sustain this cycle, and maximise strike rates across the pyramid. The very best federations are also leveraging data and insights to accelerate their delivery in every pillar.

Participation

Youth Development

Transition

Domestic Competition

National Team

Participation

Goal: Enable all citizens to benefit from playing sport.

Ecosystem Requirements:

- Culture: Integrate the sport into society, encouraging regular viewership & participation (e.g., marketing of heroes).

- Access: Ensure widespread access to grassroots facilities, teams, and coaching.

- School Programs: Provide opportunities for young people to experience the sport for the first time.

- Example applications of data:

Benchmarking starting point: Quantifying penetration relative to population / interest metrics to determine extent to which the system needs to focus on base vs effectiveness

Segment analysis: Identifying geographic or demographic gaps within broader participation base to optimise investment

Youth Development

Goal: Nurture the next generation of athletes.

Ecosystem Requirements:

- Academy Structure: Balance minimum standards with freedom to innovate.

- Effective Talent ID: Identifying high-potential talent as early as possible.

- Coach Education: Harnessing coaches with the knowledge for athletes to improve.

- World Class Infrastructure: High-quality academy facilities across the board.

Example applications of data:

Evaluating academy ROI: Quantify the financial and performance outputs of different teams to identify best practices, and areas for improvement

Identifying development ‘predictors’: Isolating factors that predict future performance, to ensure more effective early talent ID

Transition

Goal: Create clear paths for players into elite sport.

Ecosystem Requirements:

- Clear Player Pathways: Establish a coordinated route from youth to the elite level.

- Alternative Playing Opps: Explore use of loans, B teams, reserve leagues etc to give the right playing opportunities to prospects.

- Culture of Trusting Youth: Encourage clubs & coaches to trust youth at a club level, rewarding managers who do.

Example applications of data:

Evaluation of development models: Quantify the success of other federation strategies to ensure evidence-based policy recommendations (e.g., outputs from B-team vs loan systems)

Identifying fall-off points: Isolating points the pathway where the relative quality of talent vs other nations decreases

Domestic Competition

Goal: Provide a platform for players to perform at the highest level.

Ecosystem Requirements:

- Compelling Domestic League: Enable the league to maximise quality, jeopardy, and connection – the ultimate drivers of commercial value.

- Stakeholder Relationships: Create a coordinated ecosystem between the federation, leagues, and clubs.

- Data-driven Talent ID: Utilise data to achieve value & quality in transfer dealings.

- Efficient Club Operations: Encourage value and impact driven recruitment operations.

Example applications of data:

Evaluating policy changes: Predicting the impact of federation-led policy changes to the quality of the domestic competition and wider objectives (e.g., homegrown player rules)

Influencing league / club policy: Using evidence-based arguments to influence wider stakeholders on issues central to the system’s success (e.g., club policy)

National Team

Goal: Optimise investment into league, franchises and players.

Ecosystem Requirements:

- What It Takes To Win (WITTW): Outline target state and how to get there.

- Defined Playing Style: Identify the right playing style and traits to maximise success.

- Inspirational Leadership: Recruit best-in-class Coaches, Directors, and other senior staff.

- Data-driven Squad Selection: Maximise the performance of the existing player pool.

Example applications of data:

Informing WITTW: Using data to ensure an evidence-based assessment on requirements (e.g., number of players, style, age distribution)

Talent ID: Using data to identify the right players and head coach for the team’s objectives

Conclusion: From Potential to Performance

Systemic over-performance is not an accident. It is the end product of a holistic, data-driven, and long-term strategy that connects every part of the ecosystem – from a school’s P.E. lessons to the national team’s tactical philosophy.

At Twenty First Group, our Predictive Intelligence enables us to identify the areas able to deliver the most impact, helping federations rally stakeholders across the game behind a strategy to ‘stretch the pyramid’.