Thought Leadership

The philosophy behind football‘s perpetual rise and The Super League’s fall

15 MIN READ

Thought Leadership

Inspired by what you’re reading? Why not subscribe for regular insights delivered straight to your inbox.

The Super League is dead.

The spectre of a European Super League has loomed large for three decades – the concept alone enough to increasingly unbalance European football with the slow concentration of resources – sporting and financial – among the bigger teams. These concessions, given every rights cycle, were designed to preserve the delicate equilibrium between retaining the involvement of European Football’s biggest and most valuable brands without creating such imbalance within existing competitions to render them meaningless.

This basically worked, for a time. Whenever the super league dial was turned up, the big teams would be given slightly greater access to European competitions, culminating in the latest adjustments to the UEFA Champions League format.

But an equilibrium may only be maintained if there is balance between the two opposing forces. It has been clear to anyone paying attention that European football has become increasingly predictable. Between 2011 and 2020, Juventus, Paris Saint Germain and Bayern Munich won 24 domestic titles out of a possible 30, and while Juventus and PSG surrendered their titles in 2021 it is hard not to conclude that this year has been a Covid-affected blip rather than a decline to mediocrity. Meanwhile the last representative in a Champions League final from outside the big 5 leagues was in 2004, when Jose Mourinho’s Porto defeated Monaco – the last time Europe’s biggest honour was won by someone other than one of the 12 founding members of the Super League and Bayern Munich. Ajax’s run to the semi-final in 2019 was so glorious because it was so unexpected, despite Ajax being a club with an illustrious European past encompassing four European Cups. On-field success for the biggest teams has further increased their commercial value relative to their domestic ‘competitors’ such that teams contribute an increasingly material proportion of the draw for any league’s media and commercial partners.

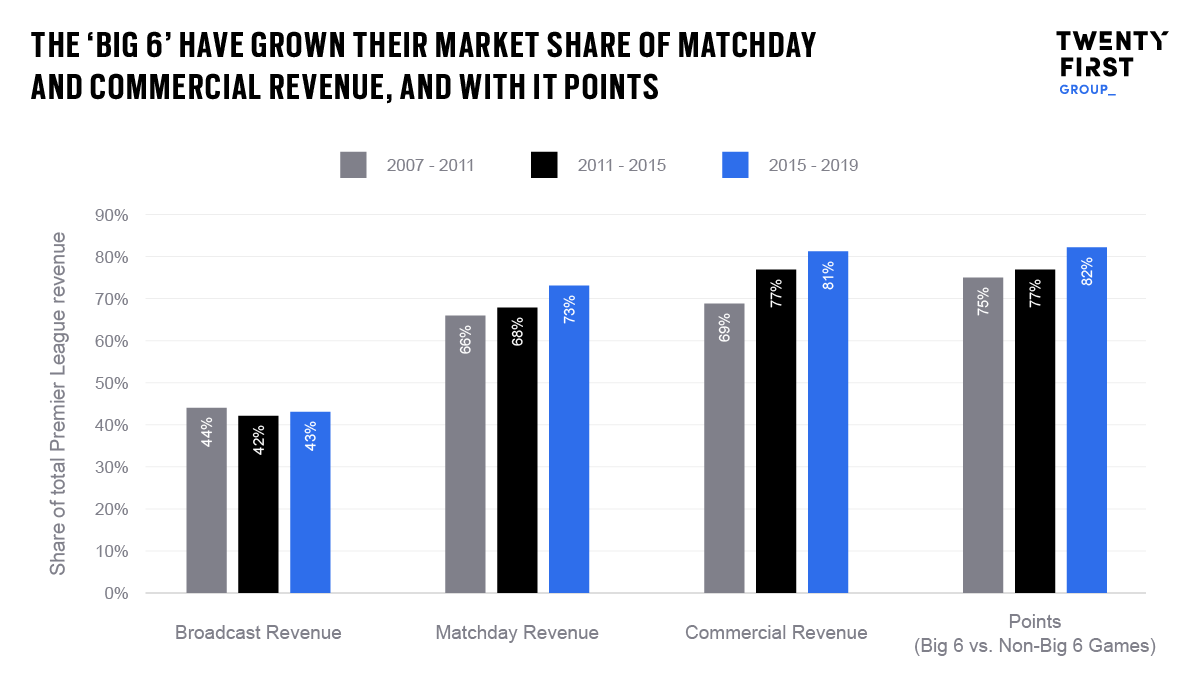

The Premier League has been the final bastion for balance among Europe’s ‘big 5’ – a truth reflected in the number of different title winners over the last 10 years (five). But while the league has been resistant to major changes to media rights distribution (the introduction of merit-based payments from the overseas media rights pool in 2017 was still relatively small in the context of overall distribution), the biggest six clubs have soared in popularity in this time, meaning that they have disproportionately grown matchday and commercial revenue, and with it their share of league table points – a trend reflected in other European leagues.

That The Super League was finally launched was not, therefore, surprising. Many in the industry believed that the game’s capitalist forces made it inevitable. What was surprising, however, was that something considered inevitable could fail so spectacularly and so quickly. That within 48 hours, something whose sheer possibility had given European Football executives sleepless nights for a generation had been put to bed for perhaps as long.

There is much to unpick from the project’s remains, but most striking is the reminder that despite its continued commercialisation, capitalism is not the only force to which European football is beholden. And maybe, just maybe, it isn’t even the strongest.

***

The US blueprint

One of the driving arguments – and likely blueprints – for The Super League is the commercial success of the American franchise model. It is true that enterprise values of MLS franchises are significantly higher than teams of equivalent quality or reach in Europe, fuelling the narrative that European football is bad at monetising their product and would be better served by the US model. But this is overstated.

First, expectations of the monetisation opportunity are often unrealistic due to inflated estimates as to the size of European clubs’ global fan bases. Analysis of football’s average revenue per fan only stacks up if you have an accurate view of the denominator. Manchester United, for example, reportedly have over 1 billion fans meaning they make around 60 pence from each one on average. This is off the back of a survey in which 54,000 respondents were asked to name their favourite football team. But being aware of something and being a fan who is willing to pay to demonstrate a connection are two different things and assuming that Manchester United have the passionate support of 15% of the planet feels optimistic. Their social following perhaps presents a more realistic view which at c.150m is hugely significant but materially lower.

Second, some European clubs are already more effective than some of the world’s most commercially successful entertainment products. One season of Game of Thrones – one of the most successful entertainment products in recent history – generates about the same amount of revenue as Arsenal does each year. Game of Thrones managed it for 8 seasons, while Arsenal may do it forever.

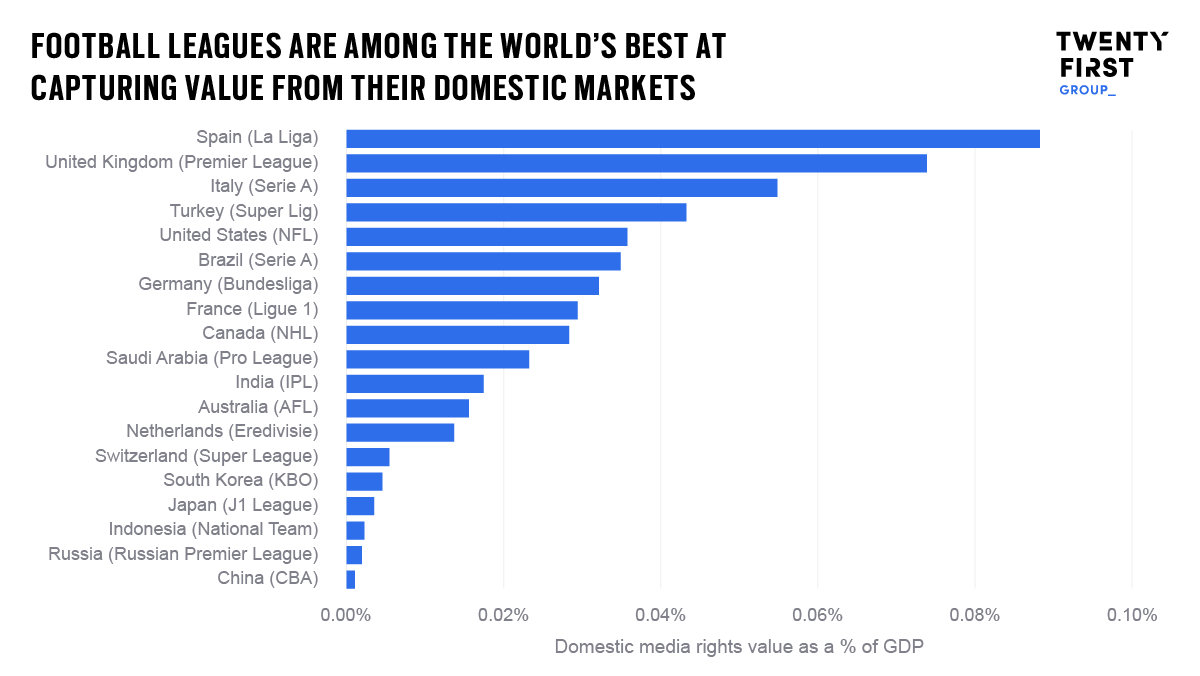

Third, while domestic media rights deals for sports like the NFL are enormous – especially on a per game basis – they have the advantage of being marketed to the world’s biggest economy. When measured as a % of GDP, the Premier League, La Liga and Serie A actually out-performs the NFL suggesting that European football fans are often willing to spend more per capita to watch football than Americans are to watch NFL.

Finally, the European and US systems are fundamentally different and what is deemed authentic sport – the way in which quality, jeopardy and connection is delivered to fans – is different too. US leagues don’t sit on top of a professional sports pyramid – they sit astride a college system where narratives are created through the draft. As a result, teams can’t rise up and fall down the pyramid – narratives are limited to winning, with the threat of decline or even extinction prevalent in European football absent. Outside of the top teams, fans expend their energy and passion on college teams. This influences enterprise values for professional teams both through limiting the downside of ownership and through scarcity. The number and status of clubs is controlled by the league system – like a sort of sporting Blockchain – while in the free-wheeling, free-market world of European football there are any number of clubs for sale, all of which have a chance of one day becoming a ‘superclub’.

None of this is meant to refute the fact that opportunities for commercial growth abound – it is simply to point out that where European football currently stands is perhaps not as bad as is sometimes supposed.

The logic behind the commercial model

The great irony of the project was that it was conceived to maximise revenue for participating clubs but that those who are the ultimate source of all club revenue – the fans – weren’t consulted and didn’t like the idea very much. UK-based creative agency Ear to the Ground has since conducted research that revealed that 80% of Gen Z fans – the group (aged 16-24) to whom the concept was primarily targeted – were unsupportive of the new competition. The reaction to the project was one of the few times football fans have been truly united in pursuit of a coherent, common goal.

But the proposal is backed by both logic and evidence, of a kind. While not directly consulted, fan wishes were interpreted through their actions evidenced in viewing figures, social media following and engagement. This evidence supports the logic that revenue growth for the biggest clubs would be best achieved by pooling their commercial strength into a single competition into which they are guaranteed access each year.

It is certainly true that more people tune in to watch Manchester United vs. Liverpool than Burnley vs. Brighton, and the relative social following of the world’s biggest teams dwarfs that of mid-table teams in Europe’s top divisions. This is true of both a domestic and international audience, although is even more acute among younger, international audiences where ties with clubs tend to be based purely on the quality and brand strength of both the clubs and star players. There is little reason for a fan in China to watch Sheffield United, while the prospect of watching Raheem Sterling for Manchester City is all the more appealing.

The logic holds, therefore, that if there can be more matches between the world’s biggest teams, more people will want to watch, resulting in higher subscription revenues for broadcasters, higher media rights values for competitions and higher revenues for clubs. This kind of logic holds true in other forms of entertainment, namely film: people like Iron Man and Thor? Put the two together and you get, among others, Avengers: Endgame, the second-highest grossing film in history. So far, so clear. But in football this only works in the context of an authentic competition and The Super League was not perceived as such.

***

It’s not sport

Much of what has been written since the end of The Super League’s cameo has focused on the communication strategy, rightly pointing out how badly the whole thing was handled and how surprising this was given the experience and competence of many of the people involved. It may be true that the project would have had a better chance were the founding members more committed to persuading stakeholders on the idea’s merits rather than preemptively defending their legal position. But the project was destined for failure, not because of the botched launch, but because it was an entertainment product marketed to sports fans, and as such was simply a bad idea.

It is our belief that for professional sport to be commercially successful, it must be authentic and to be authentic, sport must inspire fans through quality, excite fans through jeopardy and connect with fans through what it means – to both fans and players – to win. The Super League was destined to be the highest quality football competition on the planet. Tick. But jeopardy was undermined through guaranteeing access to the founding members each year, removing the punishment for failure. Jeopardy is what happens when high stakes meets uncertainty and allowing clubs to lose on the pitch without any material consequence off it meant that games outside of the title race wouldn’t have mattered. More significantly, jeopardy within domestic leagues would have been materially undermined, rendering 9 months and up to 380 games of football next to meaningless. “It is not a sport where the relation between effort and success does not exist. It is not a sport where success is already guaranteed, it is not a sport where it doesn’t matter when you lose.” In his press conference following the announcement, Pep Guardiola succinctly articulated the significance of jeopardy’s absence.

But that fans didn’t feel a connection to the competition was a bigger issue still and was largely for two reasons. The first was that the sporting credibility of the competition was undermined through the qualification criteria. Instead of being based on a sporting meritocracy the participation of the founding members was determined by their commercial clout and historic, rather than current, success. Today’s Champions League is legitimate (albeit not without issues of its own) because the participating teams deserve to be there because they are the best teams from their respective nations at that given moment.

Second, the perception was that the games would have lacked the proper context as the competition lacked meaningful history. Fans have a connection not only with the players and clubs, but also with the competitions in which they compete – clubs are playing on a platform that would still matter even if some of them weren’t there. It’s a bit like watching Coldplay headline Glastonbury. It’s more meaningful seeing them perform on one of music’s most iconic stages than watching them play a random stadium in a one-off event. The reason being there is a context to their performance that enhances its significance. And likewise, Glastonbury is still Glastonbury even without Coldplay.

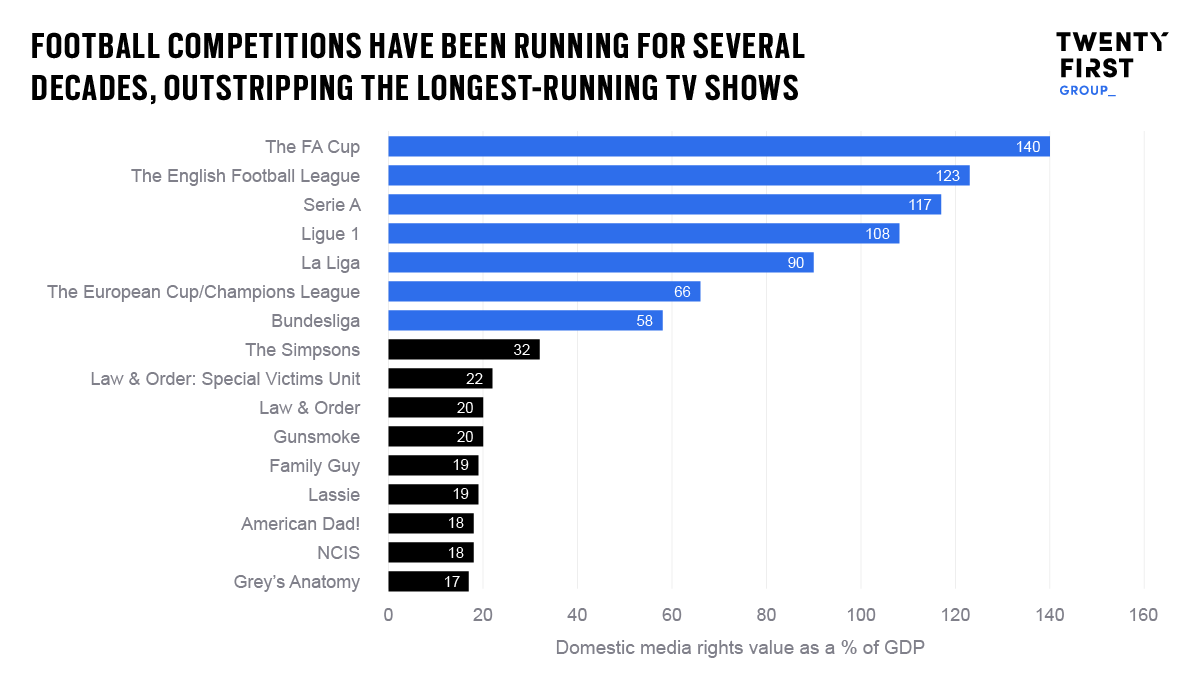

History matters. Historical context is one of the key things that differentiates sport from entertainment. The top flight of English football has been running under various guises since 1888. While the format, the teams, the narratives, the quality, the style of football have all evolved over that time, the fundamentals – that of a sporting competition between England’s best football teams – remain the same. That’s 123 seasons. Compare that to the longest running scripted TV Show – The Simpsons at 32 seasons (and counting) – and you begin to see that there is something about sport that makes it different. How can an entertainment product that is fundamentally the same as it has always been continue to capture the imagination and elicit the passion of so many fans such that club affiliations are passed down within the family for generations?

The reason is that it finds a way to continue to matter. The product evolves, narratives shift, characters change, standards are set and then reset and with each passing year the historical tapestry upon which the competition is based becomes ever so slightly different, ever so slightly richer. The passing of time is treacherous to a TV show. Plots become stale or out-dated. Values shift. Actors age. To sport, the passing of time is essential – the longer it runs, the greater the authenticity, the greater the narrative, the greater the meaning of victory. This is not to say that new competitions can’t work – the success of, for example, the IPL would suggest otherwise. It is simply to acknowledge that for change to deliver positive outcomes it must improve the bits that aren’t working and preserve the bits that are. In the case of the IPL, fans were underserved by a high quality T20 competition featuring the world’s best players. The same cannot be said for European football.

Authenticity. Credibility. Evolving and ever-changing narratives in an appropriate historical context. These are all key things that underpin the fans’ connection with the European football product. In limiting access and operating outside of football’s existing structures, The Super League ignored the foundations of the sport’s success and in so doing was casting itself as entertainment first and sport second. As such, it may have prevented it from standing the test of time.

Ultimately, in being motivated more by money than sport The Super League concept revealed the paradox central to its failure – to create stability in revenue, access needed to be guaranteed to Europe’s biggest clubs. But in guaranteeing access, authenticity was lost along with credibility among the competition’s customers – the fans.

***

So what now?

In the wake of The Super League, one of the challenges that football now faces is the subsequent glorification of the status quo – the idea that just because something worse has been proposed, that we should accept what we have. In real life, no one would accept a poke in the eye just because they’ve been offered a punch in the face. There are significant challenges with where football is today. Europe’s leagues are becoming increasingly unbalanced and predictable, undermining the principle of jeopardy that is so critical to successful sport. Teams are having to balance a desire for on-field success with the necessity to operate on a sustainable basis – something made much more challenging in a zero-sum league structure which makes spending no guarantee of success. The way in which fans are consuming and engaging with content is changing, driven by a combination of technological innovation and increasing competition for their time.

These, and more, are issues that need resolving and there are many sensible options being explored – cross-border leagues, spending controls and new commercial models among them. But in addressing these issues, recognising what has made football so successful for so long is critical. Football mustn’t burn the house down to smoke out a rat. In looking to move forward we must interrogate, define, understand and protect the things that have got football to where it is today.

Organisers of competitions always need to strike the balance between the sporting and the commercial. Quality, jeopardy and connection, where connection is derived from a credible competition played within an appropriate historical context, remain the key things that determine a sport’s commercial success. Those who ignore this intangible truth in a narrow pursuit of financial return may not only fail to deliver the projected financial return, but may also do lasting damage to one of the world’s great sources of entertainment.

Speaking about Atalanta’s qualification for the 2019/20 Champions League, Andrea Agnelli, one of the key players in The Super League saga, posed this very question. “I have great respect for everything that Atalanta are doing, but without international history and thanks to just one great season, they had direct access into the primary European club competition. Is that right or not?” The answer, delivered to Agnelli in emphatic fashion by fans across Europe in response to The Super League, is clear: ‘Yes’.

This article was originally posted in the Off The Pitch.