Thought Leadership

Reimagining the financial future of lower-league football

15 MIN READ

Thought Leadership

Inspired by what you’re reading? Why not subscribe for regular insights delivered straight to your inbox.

It’s pretty much like a death in the family.” Macclesfield Town veteran midfielder Danny Whitaker’s reaction to the demise of his beloved team illustrates the devotion that many have to unglamorous football clubs the world over. The case of Macclesfield, who have been expelled from England’s National League and wound up following a ruling from the High Court, is a grisly warning for just how serious the impact of the ongoing pandemic might be on the world’s most popular sport.

Macclesfield may be the first of many, with clubs up and down the country locked in a battle for their very lives – pleas both to the Premier League and the government for financial support are becoming increasingly desperate as the prospect of fans returning to stadiums recedes further into an opaque future.

But the pandemic has merely accelerated a problem that had already taken root. Bury FC, for example, disappeared from view on August 27, 2019, months before the pandemic took hold and at a time when much of the world was blissfully unaware of ‘R’ numbers, exponential curves, and circuit breakers. Many clubs were already swimming naked before the pandemic forced the tide out.

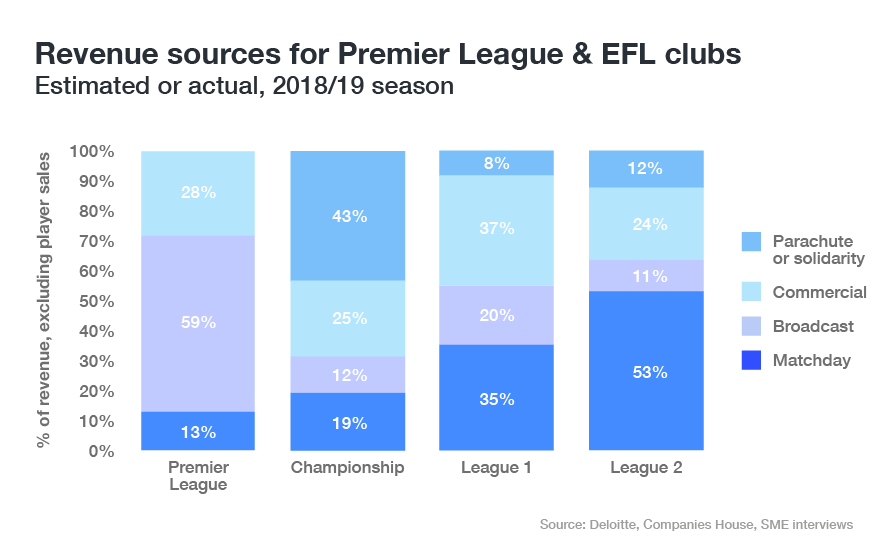

The situation has instigated urgent and overdue discussions around what may be done to preserve clubs that continue to play a significant and long-standing cultural role for communities across England. The EFL have already imposed a salary cap on Leagues One and Two – the professional leagues most impacted by the pandemic given their reliance on matchday income.

Project Big Picture, the draft proposal compiled by the owners of Liverpool and Manchester United alongside EFL chairman Rick Parry, offered a more holistic solution. The proposal’s fierce opposition and subsequent rejection was as much a reaction to the clandestine and self-interested nature of the plan’s conception as a thoughtful and constructive critique of its details, many of which had merit.

While dead, the proposal has had a positive effect through emphasising the need for radical thinking and creative ideas and highlighting the fact that a salary cap alone is not sufficient to solve the EFL’s problems. It has also shown that change will only come if ideas are supported with robust evidence and conceived in collaboration with football’s stakeholders via a structured, transparent process.

Absent across all of the proposals to date, however, has been a clear articulation of the actual problem that we are trying to solve. Solutions have been proposed, but most of the time these are aimed at alleviating symptoms rather than targeting a well-defined root cause. To devise solutions that will protect and preserve some of the country’s most beloved institutions for the long term, we need a clear understanding of why clubs were on an insecure financial footing in the first place.

Why are we here?

Albert Einstein once famously said, “’If I had an hour to solve a problem I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions”. If he were here today and was, for some reason, applying his substantial brain to this particular problem, he would probably be trying to better understand why clubs have continually fallen into the same traps of overspending, often operating with wage-to-revenue ratios of over 100 per cent.

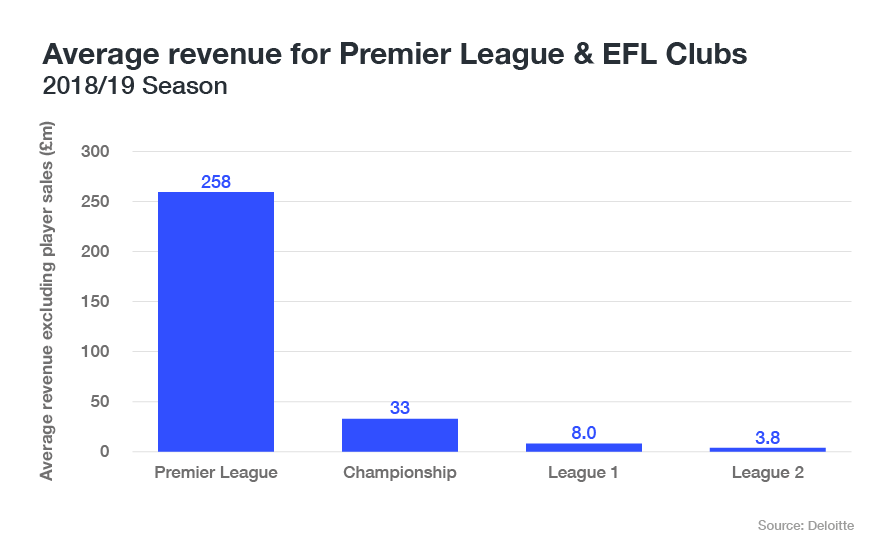

He may conclude that clubs are simply incentivised to do so. The concentration of wealth and glory is so top-heavy, the revenue jumps received on promotion so significant, that clubs are encouraged to speculate to increase their chances of climbing the ladder.

This promotes the idea that satisfaction may only be attained through promotion. But league football is a zero-sum game: when everyone spends, no-one benefits, meaning that clubs have to overspend just to keep up.

Solving this issue is a significant task and requires the football world to build consensus through defining some shared principles that reflect the true nature of the problem in order to shape solutions in the right way.

In defining incentives as the core issue facing the EFL, we have explored some solutions to address this specifically in the key areas of media-rights sales, spending restrictions, club purpose and competition format. This is not intended to be a comprehensive solution, but instead serves to explore how solutions may be tailored to try and address the incentives problem for the long term.

Reducing the incentive through revenue growth via media rights

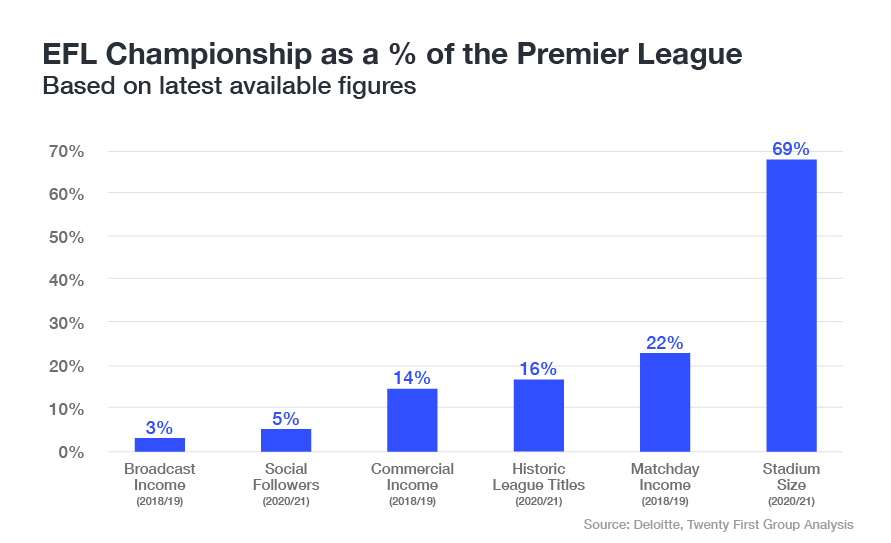

The obvious solution to the incentives problem specifically would be a significant redistribution of broadcast money to reduce the concentration at the top of the pyramid. But this is both unrealistic and unfair in an industry founded on the principles of meritocracy – it is the Premier League’s clubs that generate the game’s wealth, meaning that they should generally be the ones who share the spoils. As a result, some form of cliff-edge is reasonable in the context of the divisional structure of the pyramid.

Instead, the gap may be closed through growing the revenue of EFL clubs. There is evidence to suggest that there is unrealised value in the EFL’s media rights. Achieving a greater yield on this value should take precedence over redistribution. Creating a narrative that reflects the inherent excitement of the competition, optimising the schedule to limit competition for EFL matches and enhancing the process by which media rights are sold may help to grow EFL club revenues, closing the gap with the top of the pyramid.

Managing the incentive through spending restrictions

As well as growing revenue, some form of restriction on spending is needed – enforcing some restraint on an industry prone to emotional and optimistic decisions makes sense. The EFL have done this through imposing a ‘hard’ cap on Leagues One and Two but they may be better served by a ‘soft’ cap linked to revenue received from the previous year. This would enhance the new system which we believe has some major flaws.

The first and most significant flaw relates to the way the cap has been applied. A hard cap applied across the division regardless of club revenue limits the upward mobility of ambitious, efficient clubs through removing the positive incentive for clubs to develop their business models. As Simon Hallet, owner of Plymouth Argyle, recently wrote in his letter to fans: “We voted against [the salary cap] on the grounds that our strategy has been based on investing in revenue-generating assets, so, in normal circumstances, we should be able to use those extra revenues to fund extra spending on our first team squad. Such extra spending should give us an advantage versus other clubs competing in League One.”

Linking the cap to revenue will maintain the incentive for clubs to invest in a sustainable way – by forcing clubs to grow revenue in order to fund their performance ambitions. A version of this was already in place through the Salary Cost Management Protocol (SCMP), but this linked spend to the promise of revenue rather than the receipt of it, making it ineffective and difficult to enforce, as did the fact that the process by which the cap was monitored was entirely manual and didn’t utilise any of the available technology to provide a dynamic view of a club’s state of compliance.

The second flaw is that the salary cap does not remove the incentive to overspend – reaching the Premier League still brings huge financial benefits – it merely weakens the clubs’ ability to act on it. While the incentive remains, clubs will find creative ways to satisfy their sporting ambitions at the expense of compliance. Derby County, Sheffield Wednesday and Aston Villa have all courted controversy through the sale and leaseback of their stadiums and there have been numerous examples of financial fair play breaches among Europe’s biggest clubs. Perhaps the best example is rugby club Saracens, whose success in winning multiple trophies was effectively the result of finding ways to pay their players outside of Premiership Rugby’s salary cap.

Third, the gap in the size of the proposed cap between League One and the Championship creates a substantial cliff between the divisions. The existing revenue cliff between the Premier League and Championship creates a number of well-documented issues for clubs who fall off, with parachute payments accounting for the greatest share of revenue across the entire Championship, despite being received by only a few clubs. Avoiding a similar situation between the Championship and League One should be a key priority.

Some form of soft cap linked to revenue received the previous year with some sensible adjustment for clubs that have changed divisions would be more effective at enforcing a degree of sensible cost control while avoiding these flaws. It is enforceable being based on audited accounts, retains the incentive for clubs to grow their business, and will shrink the cliff between the top of League One and the Championship by rewarding revenue growth with additional budget to invest in the playing squad.

Redefining incentives for clubs in the EFL

Even with these changes, redefining what it means to be an EFL club is ultimately the only way to truly remove the incentives problem. This requires us to ask some tough questions around what the purpose of the EFL actually is. Is it simply to act as the route to the riches of the Premier League, or is it something else? The answer to this question will help to determine what other measures should be implemented to best serve the league. There are a number of things that the EFL does for English football that are not truly recognised, celebrated or enshrined in the governance of the league.

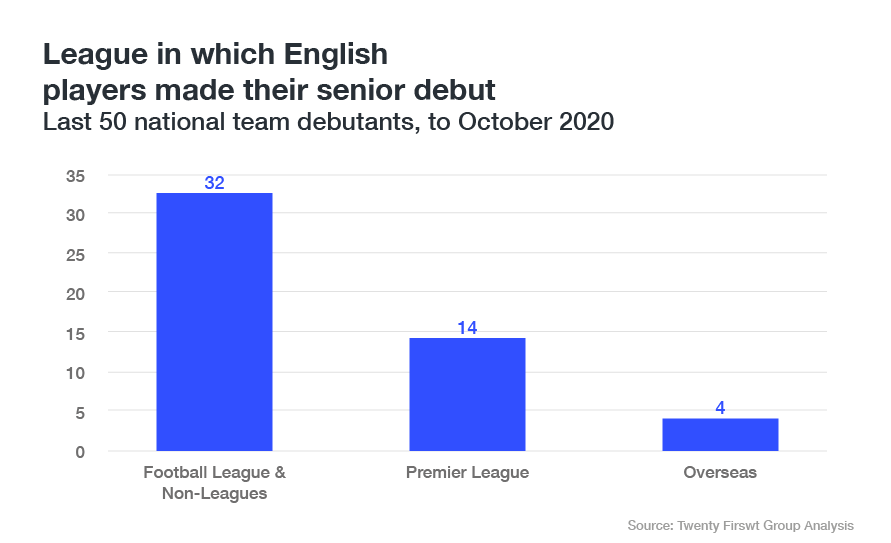

One example is as a factory for the development of English talent. Nearly 4 in 10 U23 English players in last season’s Premier League made their senior league debut in the EFL or non-leagues. More strikingly, 32 of the England national team’s last 50 debutants made their league debuts at these levels. Were the EFL to recalibrate its modus operandi as a pathway for players rather than clubs to reach the top of the game, greater focus would be given to protecting the incentives for these clubs to successfully develop players and be adequately rewarded for doing so.

Developing clubs could, for example, be entitled to a proportion of all future transfer fees even if the player is no longer registered to their club (as a mandatory sell-on). While an imperfect system, transfer fees have effectively been established as the game’s wealth redistribution mechanism and tweaking this to reward developing clubs may have long-term benefits. Alternatively, there could be an FA-funded payment for each international cap received, in recognition of the developing club’s service to the national game. Both approaches would reward clubs for success and preserve the incentive to develop talent. If a strong case can be made that the EFL is the foundation upon which the Premier League’s and National Team’s success is built, there may be greater scope for collaboration between all parties.

Community centres

A second consideration is the role that EFL clubs play in their local community. Reframing the purpose of the Football League as being the custodian of some of the country’s most culturally relevant institutions would change the way that the league and its clubs are governed.

Instead of being incentivised to win, clubs could instead be encouraged to engage more effectively with fans. Incentives could be created around the achievement of simple metrics separate to performance such as maintaining high (or improved) attendance levels, for example. This could be evolved into measuring the effectiveness of community outreach through things like collaborations with schools etc.

Of course the reward must be sufficiently attractive in order to shift behaviour. In the absence of community programmes delivering significant short-term revenue, rewards could be non-financial. For example, the most locally in-tune EFL teams could be allowed to select a third round FA Cup tie of their choice. This would enable them to choose between likely progress in the competition in selecting a weak opponent at home, or a payday and exciting day out for fans in selecting an away tie at a Premier League giant. This would also serve as a means to highlight the club’s success in the community, which may drive greater interest and income at the club in future seasons.

All this would require fans to buy in to this reality but this should be easier where clubs are less focused on progress up the pyramid and more focused on progress in their community.

Purveyors of an authentic football experience

A third way to think about EFL clubs is that they are to the Premier League what the pokey restaurant tucked away on a side street is to the Michelin star establishment in the swanky part of town. The food may not have the same refinement or quality of ingredients, but the experience is warm and authentic.

Importantly, these smaller restaurants aren’t measuring their success based on whether they can compete with Nobu or achieve a Michelin Star. They have defined their own version of success which may reflect a different but no less valid type of ambition, perhaps involving a deeper more personal relationship with their customers, for example.

For EFL clubs, perhaps performance on the pitch could be more incidental to the true purpose of the club – cultivating a meaningful relationship with fans who simply enjoy watching the team play, win or lose. A banner on display at a recent Union Berlin match reading “Crap, we’re getting promoted” demonstrates that some fans measure the success of their clubs very differently. This approach doesn’t preclude on-field success either – Union Berlin still achieved promotion without making it the be all and end all of the club.

Changing the incentives through competition restructure

The competition’s structure must reflect this change in club ‘purpose’ in order to make it stick. As long as the pyramid rewards success exclusively through promotion, clubs will do what it takes to achieve it. Changing the league structure should therefore achieve two things – the first is to weaken the relationship between spending and success to reduce the incentive to spend unsustainably. The second is to create something to play for that matters enough to constitute success, but not so much to create the same issues of sustainability across the league today.

Reducing the relationship between spending and success requires the structure to essentially increase the role of luck in determining those who are promoted or relegated. Psychologically, this is an extremely challenging concept for most fans especially given the desire for meritocracy, but we should acknowledge that luck already plays a significant role in determining the outcome of football matches – as a low scoring sport, one third of football matches are not won by the most deserving team. This is one of the key reasons why football is the world’s most popular sport.

There are also several precedents where formats celebrate luck and benefit as a result. The knockout rounds of the World Cup and the Uefa Champions League are substantial, with the draw and football’s low-scoring nature creating an unequal playing field often rewarding the luckiest, as opposed to the best, team. Over the last 12 years, only 25 per cent of Uefa Champions League winners were rated as the ‘actual’ best team in Europe in 21st Club’s World Super League. Barely half of the time the winner isn’t even the domestic champion. Few would argue that 2011-12 winners Chelsea were a better team than Manchester City, given that they finished 25 points below them in the Premier League table. There is no reason, therefore, why a format that promotes the role of luck in the right way, thereby reducing the relationship between success and spending, should be unacceptable to the EFL’s stakeholders.

Reducing the influence of spending needn’t reduce the significance of what the teams are playing for either. The key is to focus the attention of owners on a version of success that rewards clubs with glory, rather than money. Creating new trophies will only work if they are awarded for the achievement of something that matters to fans, players and clubs.

With this in mind, we have developed some ‘guiding principles’, to ensure that any format alternatives take account of what is trying to be achieved. For example, the competition must promote matches that have meaning via a narrative both in the context of the competition and in the general context of the club. The format must be credible, meaning that it is simple to follow, retains sporting integrity and has reasonable competitive balance, while also reducing the incentive for clubs to overspend. In addition, and particularly in the case of the EFL, the competition must also be cost-effective for clubs to participate and for fans to follow.

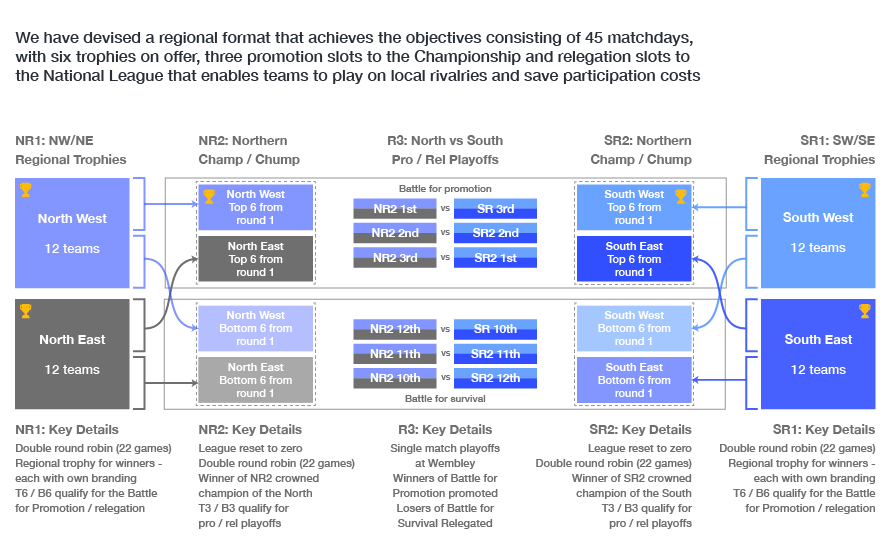

Below is a regional structure for League One and League Two as an example of the type of structure that would adhere to these principles.

Through a statistical simulation of the new format, we find that it delivers against our guiding principles in the following ways:

- Meaning: Increases the number of trophies available to teams from two to six, providing new opportunities for teams to win something meaningful, while also delivering the same percentage of ‘meaningful’ matches (i.e. non-dead rubbers) which is one of the most valuable aspects of the existing format

- Credible: Utilises a format already widely accepted across the game (double round robin with playoffs), while the regional structure is mirrored across Europe and was in place in England until 1958

- Reduces the incentive: Reduces the odds of promotion for the third tier’s best team from 80 per cent to 57 per cent thereby weakening the incentive to spend indiscriminately on wages – this should also reduce the incentive for clubs to find ways around any spending restrictions that are in place

- Cost-effective: Reduces the total travel distance for teams by 45 per cent, reducing cost of travel costs, benefitting the environment and better enabling fans to follow their teams home and away.

This proposal leaves the Championship format as it is. The Championship already produces some of the most compelling football in the country (the conclusion of the 2019-20 season was a great example of this), and being one of only two national leagues in the country opens the door for closer alignment and collaboration with the Premier League for their mutual benefit (this is broadly the structure adopted in Spain, Italy, and France, where overspending is generally less of an issue). The soft cap would enable clubs to naturally close the gap in wage spend between the promoted and relegated teams, while the proposed format, if effectively sold, should grow the value of media revenue for participating clubs, further closing the gap while also giving owners something to play for other than the prospect of promotion.

More thought and analysis is required to validate a number of these assumptions and build the necessary confidence and consensus for change, but the combination of the soft cap, effective media-rights sales, redefining the purpose of the EFL and a creative and compelling restructure of League One and League Two may form the basis for a comprehensive solution sufficient to reverse the march towards financial collapse.

Conclusion

“It’s got absolutely nothing to do with Covid,” said Whitaker. “If anything, the coronavirus actually prolonged the club’s life [because of financial support]. It’s been mismanaged from top to bottom. It could have been avoided, and should have been avoided. Especially after what happened to Bury.”

It is hard to miss the anger in Whitaker’s words when contemplating the fate of Macclesfield Town. It is too easy both to blame the coronavirus for the financial mess facing the EFL’s clubs, and to assume that all problems will be resolved by the implementation of a simple salary cap.

Substantial problems require substantial solutions. A route out is achievable but will require commitment to address the issue in a comprehensive way, creativity to identify innovative solutions, and courage to implement the type of radical change required to be successful.

“I’m a fan at the end of the day. I was a fan before I started playing for them, and I’ll always be a fan. It’s been my life.” Whitaker’s affinity to Macclesfield is mirrored by fans of clubs all over the world. Anything that elicits such emotion is worth saving. We only hope that the EFL and other leagues globally have the commitment, creativity and courage to do it.

This article was originally posted in SportBusiness. You can find the original version here.