Thought Leadership

Leading from the front: unlocking value in the Women’s Super League

8 MIN READ

Thought Leadership

Inspired by what you’re reading? Why not subscribe for regular insights delivered straight to your inbox.

The FA Women’s Super League (WSL) kicks off again this weekend. With a new, three-year broadcast deal being announced earlier this year and the Barclays title sponsorship up for renewal next July, the upcoming season marks the start of a pivotal period for the league. How can the league ensure it achieves its ambitions?

Games between the league’s best four clubs (Arsenal, Chelsea, Manchester City and Manchester United) attract the biggest attendances and TV audiences. In the 2019/2020 season, games contested between these clubs attracted crowds that were 80% higher than games featuring just one of the four versus another league opponent. The difference was even starker for fixtures where none of these four clubs were involved, where crowds were a third of those at the biggest ties.

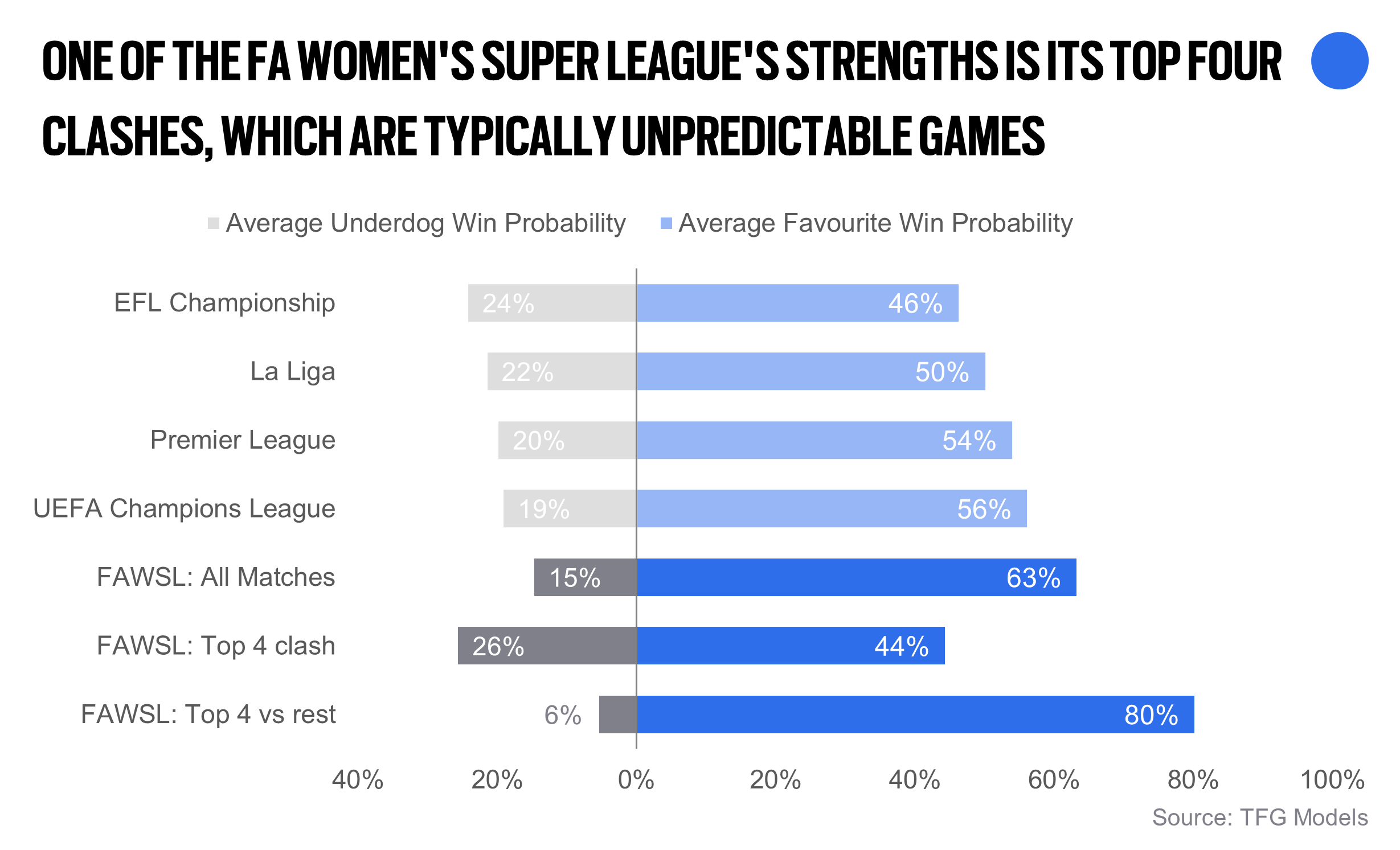

Viewers engage so readily with games between these teams not just because they offer the highest quality football, but also because they are balanced games with a lot riding on the outcome – in other words, they have the highest jeopardy too. The favourite in an average Women’s Super League fixture has a 63% chance of winning, compared to a 54% chance in the men’s Premier League. But there is a stark difference between games contested by the top four and games contested by the rest: a top four club is 75 percentage points more likely to win than their opponent when playing against a lower-ranked team. When the top clubs play each other however, the favourite has just a 19 percentage point advantage. Adjusting the competition’s structure to create more of these high-stakes fixtures would increase the appeal to fans.

An easy solution would be to add play-offs or a championship round to decide the title at the end of the year, to be contested by the top teams from the regular season. This could be anything from a US-style knockout system to a mini-league format that accounts for performance over the preceding months. We’d get more games between the biggest clubs, and in a format that necessitates every game has meaning, without necessarily diluting the importance of existing regular season matches. More games and bigger audiences would deliver greater value to broadcasters and in turn increase the value of the league’s rights. Distributing this additional revenue equitably among all teams would help to finance infrastructure improvements and higher wages. The level of the rest of the league’s teams would rise, leading to a higher quality and more evenly-balanced competition in the long-run, facilitating movement of the league’s flywheel.

This end-of-season championship round would provide a further opportunity to engage new fans. Some of the league’s biggest recent successes have come when narrative and marketing have aligned to focus around key gameweeks. The season openers following the Women’s World Cup in 2019 were held at the large stadiums usually reserved for men’s teams. The season’s first fixture played between Manchester City and Manchester United at the Etihad that September drew a record crowd of 31,200. The first Women’s Football Weekend six weeks later was carefully primed to take advantage of the men’s international break, and duly delivered further success embellished by a new record attendance: the Tottenham-Arsenal derby drew a crowd of over 38,000 people. Both fixtures also showed the merits of, where suitable, taking advantage of the connections that fans have from the men’s game, in this case local derbies.

Even away from the draw of playing in a larger stadium or against a rival team, fans responded to the marketing push; the crowd of almost 5,000 people who watched Chelsea play Manchester United that weekend remains the highest for a game played at a women’s home stadium. A well-timed mini-tournament at the end of the regular season would provide a similar such opportunity to galvanise broadcasters, sponsors and club media departments, and create more noise around the women’s game.

So is there space for these additional fixtures? The domestic club season in women’s football does not currently have the same fixture congestion as men’s club football. Chelsea Women reached the finals of both the Women’s League Cup and the Champions League last season but still competed in only 39 games in total. Their men’s equivalents also reached the finals of both a domestic cup and the Champions League, but contested 50% more games over the course of the season. The women’s game is starting to reap the rewards of better marketing, increased sponsorship and consequent higher attention from the public, but it needs to now give its biggest players and teams sufficient opportunities to write new stories and capture fans’ attention. The addition of a group stage to the UWCL is a welcome change, increasing the total number of games and ensuring big teams remain in the competition for at least six matches. For the Women’s Super League then, a championship round between the top four teams could help by adding, for example, an additional six high-value games to the calendar.

What of the risk of increasing the gap between the top teams and the rest? Most women’s teams are not financially sustainable in their own right at present and so need significant funding from their parent clubs. The fastest way to increase competitive balance in the league would be for clubs of lower-ranked WSL teams to allocate more funding towards their women’s teams. With their men’s teams fighting for each and every position in the ever-competitive English league system, clubs are unlikely to do this without good incentive. Growing the value of the league as a whole is the best way to encourage them: medium-term financial sustainability would look more realistic and the potential returns from a successful women’s team would be higher. The intention then is not to tip the balance further towards the top women’s clubs but instead to harness their brand power for the benefit of the league as a whole. For this reason, the increased broadcast revenues would need to be relatively evenly distributed across all teams, especially given the biggest clubs would likely realise growth in matchday and commercial income from a post-season competition.

There could also be more novel ways to grow the league’s reputation. The WSL has a fantastic example of success close to home in the Premier League. But to emulate this success, it doesn’t need to stick to the exact same formula. The NWSL, the USA’s professional women’s league and home to many of the world’s best players, operates on a different calendar to the European leagues. This presents the opportunity for the top leagues to collaborate more closely than in the men’s game. While a Premier League gameweek takes place every 7 days on average once the season kicks off, the average gap between WSL gameweeks is 11 days. Condensing the league’s fixture to match the frequency of the Premier League would save almost three months’ time from the schedule and could open up the possibility of players competing in both England and the US or in an intercontinental club tournament between teams from multiple leagues. Growing the value of women’s domestic football on both sides of the Atlantic would then become less of a zero-sum game.

The growing power of the wealthiest clubs dominates all debate over the future of men’s football. And while there is inequality in competition in the women’s game, women’s football can learn from the men’s game’s mistakes by using the brand strength and quality of its biggest teams to move the whole sport forward. Innovating now could lead to compound returns down the line. Waiting longer to experiment risks getting stuck in the structures of the men’s game and a failure to capitalise on the huge opportunity recent investment has handed to the sport.