Thought Leadership

Column: The pitfalls when evaluating a successful academy– there is a holistic financial model that tells a significant story

9 MIN READ

Thought Leadership

Inspired by what you’re reading? Why not subscribe for regular insights delivered straight to your inbox.

“We don’t say it’s a business plan, it’s a football programme,” Ajax CEO Edwin van der Sar told The Guardian in September, speaking about the club’s phenomenally successful academy. “We want our success with the players we educate. And if in two, three years we win trophies with them and they get a higher level, the interest of other clubs should be there. And those clubs should be bigger. After two to three years, it’s time to move on.”

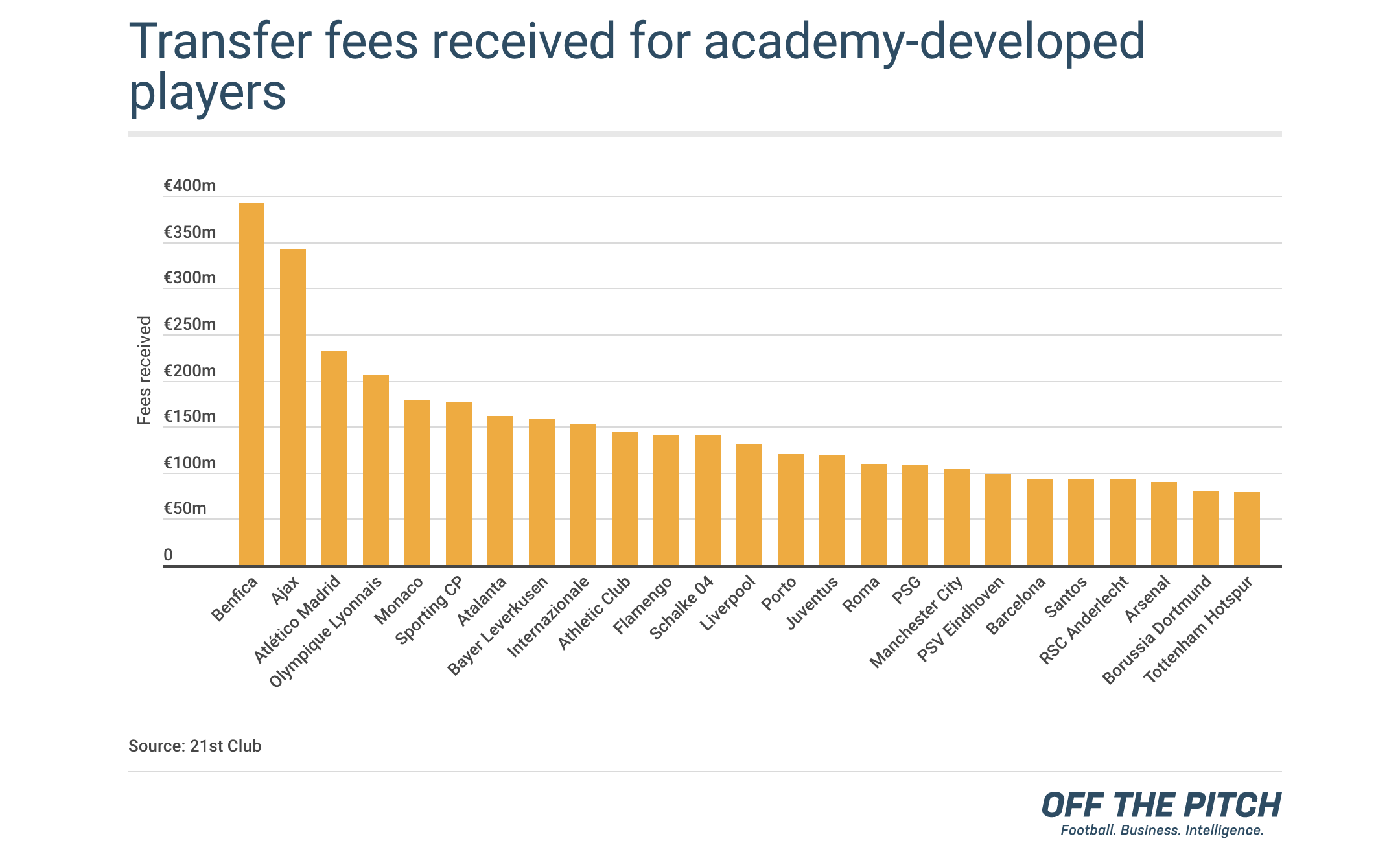

In the past six seasons, almost no club has done this better than Ajax. They’ve generated €342 million in reported transfer income from the sale of players who passed through their academy; nearly 50 per cent more than the next-best club, and only €50 million shy of the top-ranked club Benfica (who can thank João Félix for a third of their income). The club has been able to increase its overall revenue by 42 per cent just through the sale of academy products.

It may not be called a business plan, but it’s a plan most businesses would be more than happy to replicate.

Clubs revisiting their spendings

Ajax are rightly heralded as world-leaders in talent development. No one inside the club would doubt the value that their academy delivers; an ECA report from 2012 revealed that the club spent €6 million per year on their youth setup, meaning that even accounting for a potential rise in costs since then, the club has developed a hugely profitable operation.

Most football clubs, however, cannot tell the same story as Ajax. Club CEOs often grapple with quantifying the return on investment in their academy. This is especially true in England, where clubs graded Category One in the Elite Player Performance Plan can expect to spend around £3 million per year on their academy, with some of the biggest clubs often spending several times more.

With the coronavirus pandemic putting a squeeze on top-line revenue, it is understandable that clubs are considering revisiting their spending in areas where the benefit can be hard to see. Just this week, Birmingham City announced that they “will be looking at remodelling the Academy system and exploring a “B and C Team” model” despite having recently sold Jude Bellingham for a significant fee to Borussia Dortmund.

Debuts do not mean much in of themselves

Then take the Blues’ rivals Aston Villa, who since 2015 have recorded €14 million in sales of its academy products, or a little over €2 million a year. That places them 25th in English during this period, below clubs like Huddersfield Town, Fulham, and Swansea City. A superficial view of return on investment would suggest that Villa’s academy simply isn’t productive.

In the absence of meaningful transfer income to assess academy ‘productivity’, the go-to statistics for academy managers are first team debuts and minutes. But this is not a conversation that can be easily grounded in objectivity; debuts do not mean much in of themselves, and playing time needs to be understood through the prism of performance and contribution to the team.

This is of course particularly relevant for Aston Villa, with Jack Grealish being a product of the Bodymoor Heath academy. Grealish was pivotal in the club’s Premier League survival last season, and his continued form this season has even invited comparisons with Paul Gascoigne. Aston Villa may not have sold Jack Grealish – despite numerous suitors – but that doesn’t mean that their academy hasn’t delivered a return on investment.

A healthy financial return

Analytical models can begin to quantify this ‘unrealised’ value in a player. Specifically, we can ask: how much would it cost Aston Villa to acquire a player that delivers the same level of performance as Grealish, and how much more (or less) than this hypothetical player does Grealish cost?

Our player model – which evaluates the performance and value of over 100,000 players globally – suggests that a like-for-like replacement for Grealish today would likely cost Villa in the region of a £40 million transfer fee, and a further £4.5 million per year in wages. After amortising the fee over four years (a typical contract length), we’d expect Grealish’s replacement to cost £14.5 million a year, substantially more than Grealish’s reported £7 million salary.

Though Aston Villa have not sold Grealish, it is likely that they’re getting a healthy financial return on their academy in the 2020/21 season, after accounting for the ongoing operating costs of the academy this year.

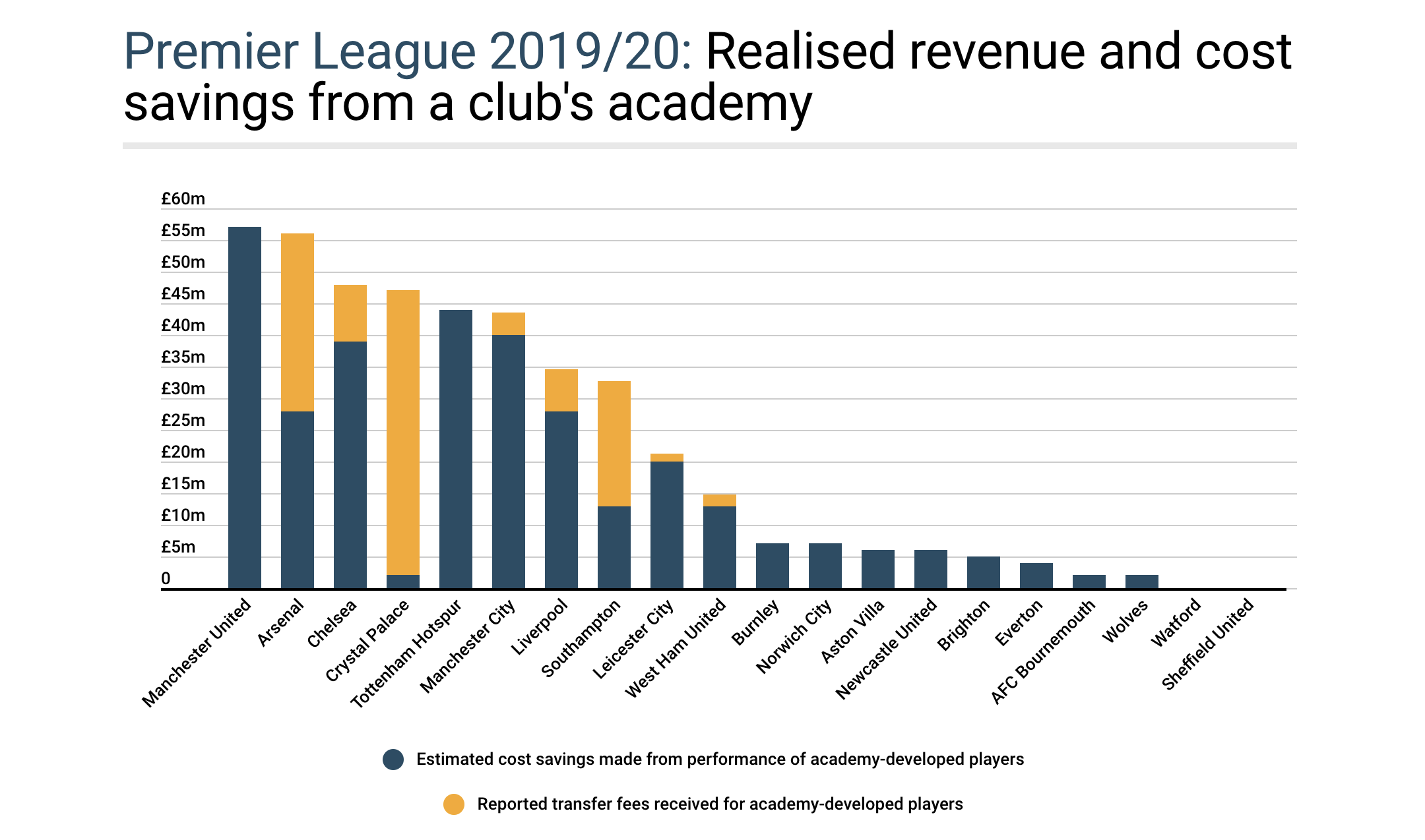

We’ve performed this analysis for all Premier League clubs in the 2019/20 season, and combined it with transfer fees received to get a holistic view on academy return on investment. Unsurprisingly, it is the biggest clubs in the country that record the biggest estimated ‘savings’ from their academy; it costs a club like Manchester United a significant amount of money to acquire a first team player, so a starter who comes from the academy with typically much lower wages and without a transfer fee is going to represent a significant cost saving.

We estimate that Manchester United’s player costs last season would have been nearly £60 million higher were it not for their academy, such were the performance levels and costs of Marcus Rashford, Scott McTominay, and Mason Greenwood in particular.

Leicester and Tottenham are different examples

Adjusting for overall cost bases, both Tottenham Hotspur and Leicester City rank well too, though in different ways. Harry Kane accounts for roughly 75 per cent of Spurs’ £44 million in savings last season; we estimate that a player of his level would cost the club over £100 million in transfer fees and £14 million a year in wages. One year of Harry Kane performance pays for the academy several years over.

Leicester City meanwhile spread their £20 million in academy savings across four players: Ben Chillwell, Harvey Barnes, Hamza Choudhury, and Luke Thomas. In 2020/21 their savings will fall with Chillwell’s sale, though clearly this is more than compensated for with the reported £45 million transfer fee – combining these figures allows a club to get a holistic view on their total academy ROI for the year.

Razor-focused on understanding return on investment

Southampton, meanwhile, continued their balance of having academy players contributing significantly in their first team – most notably James Ward-Prowse – while also generating revenue from player sales. The club will always attract headlines for the fees it has and will receive for its homegrown talent, but it would be remiss to overlook the huge value those players have added to the club on the field over the years.

For the next few years at least, clubs will be razor-focused on understanding return on investment, and even before Covid no area of a club caused more debate about ROI than its academy. Our collective obsession with transfer fees means we will always tend to be drawn into narratives about academy productivity from a pure, tangible monetary perspective.

But as we know, players aren’t simply assets to be traded, and some of the most important academy players may never sell for a fee. The smartest clubs are therefore finding ways to quantify this, and as a result will be able to realise even greater benefits from their youth setup.

This article was originally posted in Off The Pitch