Thought Leadership

Column: “A rational owner would be encouraged to leave their Champions League fate to the gods, and focus on securing domestic dominance”

10 MIN READ

Thought Leadership

Inspired by what you’re reading? Why not subscribe for regular insights delivered straight to your inbox.

“Nobody thought we would make it to the final. We were very close to winning it, but that’s football,” said Paris Saint-Germain’s president, Nasser Al Khelaifi, shortly after his team’s UEFA Champions League final defeat to Bayern Munich in August. “We are going to work hard to win the Champions League next season because that is our objective and now we believe in it more than before.”

And why wouldn’t they? In losing the final by a single goal, PSG came as close as they ever have to being crowned champions of Europe. For the Qatari-owned club, it’s a title that would bring more than just a trophy and some extra revenue. It would bring credibility, and provide the club with an allure that only 22 others in history possess.

The effort and investment made towards PSG’s Champions League push is well-documented. Over €1.3 billion has been spent on transfer fees; after accounting for transfer receipts only the Manchester clubs have spent more.

According to Off The Pitch’s Club Comparison Tool, in the 2018-19 season PSG sat fourth globally in wage expenditure. With the club having won seven of the last eight Ligue 1 titles, and their closest competitors spending barely a third of PSG’s wages, it is clear that this level of spending isn’t just in the interest of becoming domestic champions.

A better chance of winning Kansas

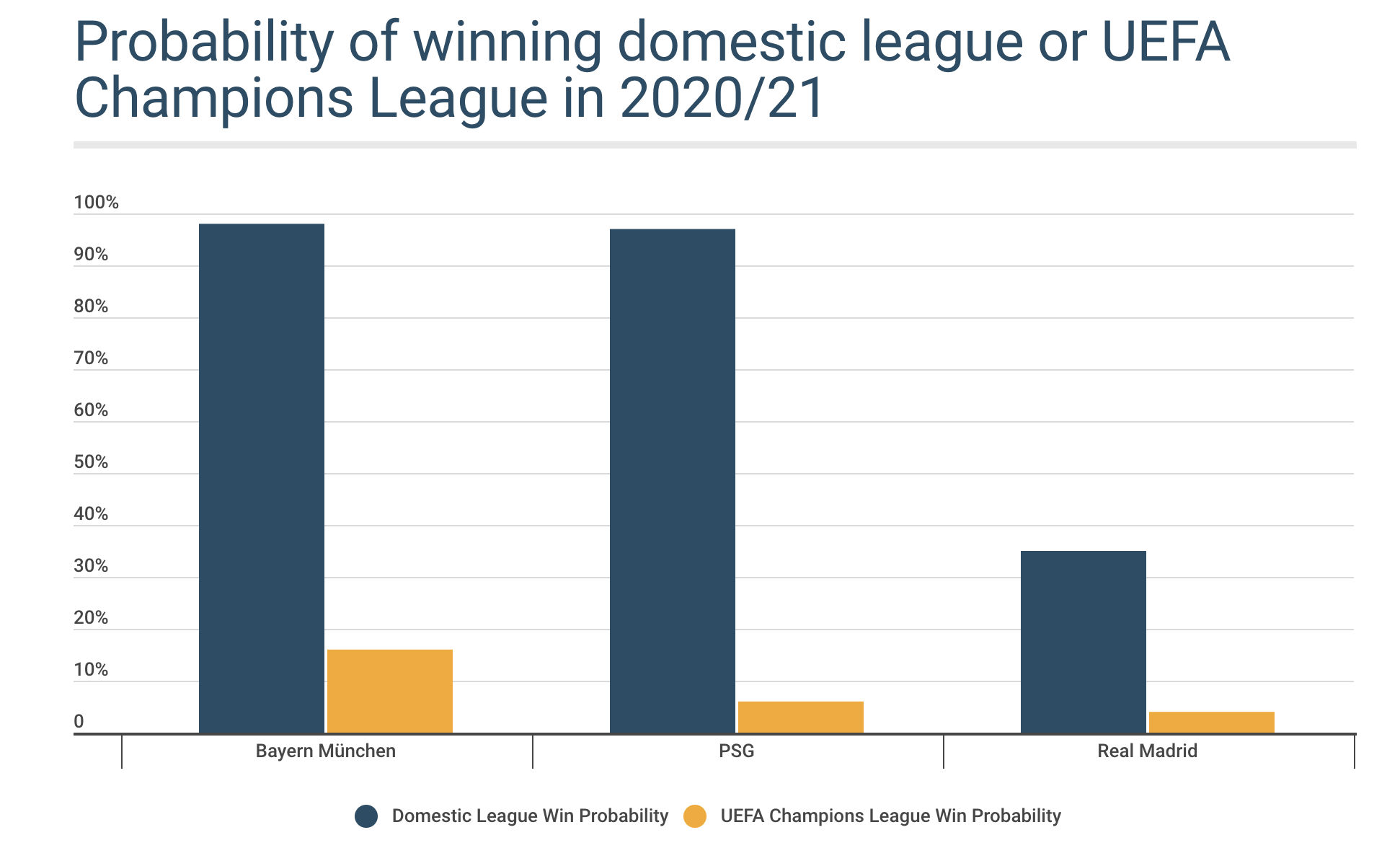

Domestic football, however, is an entirely different beast to European competition. According to 21st Club’s competition projection model, PSG entered the season with a 97 per cent chance of winning Ligue 1 – as close to a sure thing that you can get in elite sport. Their UEFA Champions League chances, on the other hand? Just six percent.

To put that into perspective, political forecasters FiveThirtyEight give Joe Biden a better chance of winning Kansas – a state that has voted Republican in 13 straight Presidential elections, and which Trump won by 21 points 2016.

No sane level of spending can materially increase their chances, either. Leaving aside the restrictions of financial fair play, let’s assume PSG invested in even better players and increased their wage bill by 50 per cent overnight. According to our modelling, their Champions League odds would increase to just 12 per cent. These odds are not much better than putting your chips on the corner of four squares on a roulette table.

It is important to say that this is not a reflection of PSG per se. Our models currently rate the French club as the third-best team in the world. In other words, not wildly different to what you might expect based on where they sit in spending league tables. It is instead a reflection of the more competitive field in the Champions League and – often overlooked – the role of luck in knockout football.

We can better understand this through the numbers. Football’s low-scoring nature means that the better team often doesn’t win a match (we can all remember games like this), and by extension they may not win championships, too.

Our statistical models however allow us to analyse underlying performance, to give a true indicator of how good a team really is, and what they ‘deserve’ for these performances.

Perhaps that is the realisation that PSG’s owners have come to?

In the big five European leagues over the last twelve seasons, the team with the best underlying performance won their league 42 out of 60 times, or a 70 per cent success rate. This means roughly 30 per cent of title winners were a bit lucky.

Over the same time period, the team our World Super League model rated as the best in Europe won the Champions League just four times, or a 25 per cent success rate.

In recent years those success rates have diverged even further. It may be no surprise to learn that over a 30-plus game season the better team tends to (but not always) wins, whereas in a 13-game semi-knockout tournament they do not. But the difference is stark enough to suggest that, if presented with the facts, a rational owner would be encouraged to leave their Champions League fate to the gods, and focus on securing domestic dominance.

We’ve seen that the league more often than crowns the best team champions, but lower in the league table it can be far more random

Perhaps that is the realisation that PSG’s owners have come to. The recently-closed summer window was among the quietest in their nine-year ownership of the club, and it appears that Al Khelaifi’s comments that the club would “work hard to win the Champions League next season” was not a euphemism for further investment in the squad. PSG arrive at the Champions League table this month aware that no matter their reputation and skill, they can always be dealt a dud hand.

In football it simply isn’t the case

In the grand scheme of things, this isn’t a major issue for PSG. They’re set to qualify for the Champions League every year, and eventually they will clear that final hurdle. Even if they don’t, it doesn’t fundamentally alter their business model. The clubs that are instead most hurt by the randomness of football are those who are striving to get into Europe’s elite club competition.

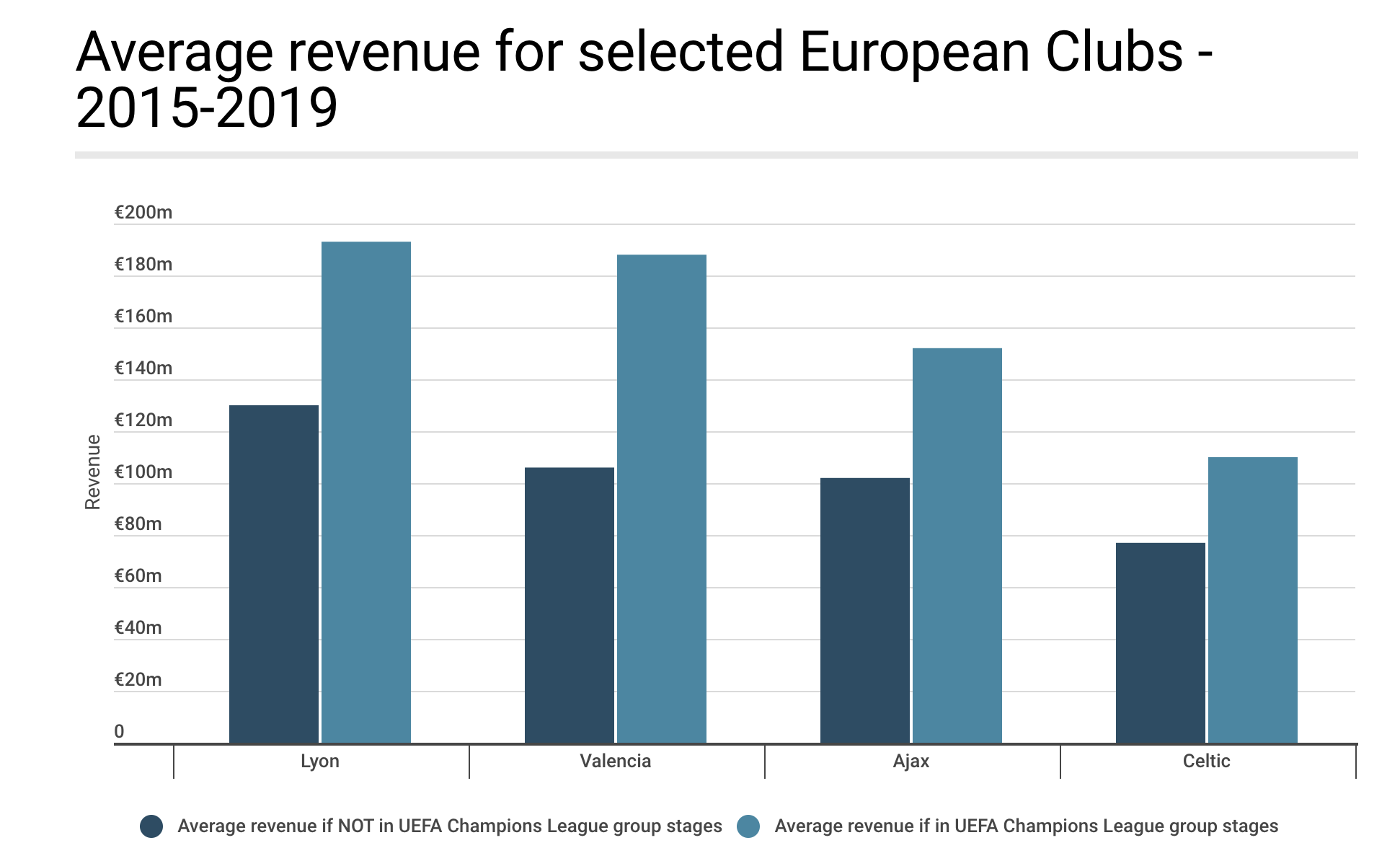

Take Ajax, Celtic, Lyon and Valencia – four clubs that have been in and out of the Champions League group stages over the last six years. Between 2014 and 2019, when these clubs were in the Champions League, their revenues were on average 54 per cent higher than when they were not. For any normal business, such revenue volatility would be highly unusual, but could at least be attributed to company performance.

In football, that simply isn’t the case. Since 2014, in the seasons preceding the Champions League group stage appearances, our models rated Lyon as the 3rd, 3rd, 2nd and 2nd best team in France. In the years in which they didn’t make the group stages, they were rated 4th, 3rd, and 2nd – virtually no difference.

We’ve seen that the league more often than crowns the best team champions, but lower in the league table it can be far more random. In Ligue 1, the division’s 3rd-best team failed to qualify for the Champions League group stages in four of the last nine seasons. In La Liga the failure rate for the fourth-best team is even higher.

Ajax and Celtic meanwhile have consistently ranked as the best teams in their countries, and have collectively failed to reach the group stages more often than not. In our global rankings, Celtic have actually been ranked higher in years in which they failed to qualify (on average 86th), than years in which they actually did (100th).

Part of the reason is that these two clubs have historically been vulnerable to the vagaries of the qualifying draws; this season Celtic could have drawn KÍ in the second round (ranked 1492nd in the world), instead they drew Ferencváros (196th) and were eliminated.

The odds are in their favour

For these types of clubs, spending with the specific aim of reaching the Champions League is a more dangerous game than it is for the likes of PSG and Manchester City spending to win it. The downside from failure is far more extreme, given the materiality of Champions League revenue to these clubs.

The solution however isn’t just to operate as if Champions League money is a lottery windfall – that is, a nice to have but not something upon which business plans should be built. Instead, it is imperative to take a long-term, probabilistic view of the challenge.

Take Marseille, for example, who qualified for the 2020/21 group stages. Going into the current season, our league projection model gave them a 29 per cent chance of qualifying for the 2021/22 competition.

Instead of breaking the bank to try and increase those odds – which we know can be fraught with danger – they might instead opt to take a five-year view on things: given this probability, they would expect to qualify for the Champions League group stages in 1 or 2 seasons out of 5.

This of course requires a steady, rational approach to ownership and management, which is far from easy in an industry that encourages short-termism through its very nature

Indeed, they have actually reached the group stages in 3 of the last 10 years. They can look to set spending at a level that would expect at least one year of Champions League football in the next five from 2021 – in some seasons this may create some budgetary pressure, but the odds are in their favour to receive a substantial sum of Champions League money at some point in this period, which nets off the fallow years.

This of course requires a steady, rational approach to ownership and management, which is far from easy in an industry that encourages short-termism through its very nature. But whether you’re a club that is pushing for titles like PSG, or one that faces volatile revenues like Lyon, it is vital to appreciate the role that luck plays – and therefore the limitations of spending – in the journey to and within European football.

This article was originally posted in Off The Pitch